Three years ago, I attended a DPI (Dutch Polymer Institute) meeting, on the question to what extent sectors had embraced the biobased economy. Everyone present made much of the achievements in their sectors; just the man from the building sector said: ‘We would like to make progress, but here I stand empty handed. Please tell me what I have to do and to whom I should turn.’ That has changed a lot now. The building trade fully plays it part, although there is much uncertainty and ignorance. And red tape. They would benefit from some support. Certainly in the crisis at hand. Government helps them with Green Deals.

‘I would welcome the roof gardener,’ Jan Rotmans says. He is a professor in transition management, and well known to readers of this site, as he pops up in every sector where developments have ground to a halt and some participants need to be put a tiger in their tanks; with his message that the world needs to, and will take another course.

Circular economy

Now this concerned the building trade, gathered in the Bouwhuis at the Utrecht fair ‘Bio Based Building’. Together with architect Thomas Rau he chastised his audience on the changes at hand, which we could best help a step further on their way. He regards the biobased economy and society as an important and necessary ingredient of the coming circular economy. Thomas Rau, a proponent too of biobased materials in the building trade, proposed another interesting vision of the future, being that we will have to leave behind us personal property and the waste producing society: we buy user’s rights such as rent, light, results of the washing process, or transport kilometers. The producer stays the owner of the hardware, retrieves the product, recycles the materials, and sells new user’s rights. This would have major implications for the building trade. It would make the customer and his specific preferences the most important factor in the building process, whereas the architect – yes, Thomas does imagine a function for him and his colleagues – will stay the connecting link. Project developers will have to leave the scene entirely; they earn a lot, do not take into account anybody’s demands, and are merely interested in building at a low, and selling at a high price. Someone asked cautiously how suppliers fit into the picture, but that would be a matter of organizing the chain.

Slow

The building trade would like to join in, but for the time being asks the ‘how’ question, as appeared in the ensuing panel discussion. Compared to three years ago, much has happened. At least the building trade has now understood that ‘green’ and ‘biobased’ are among the strong preferences of consumers/clients, and that it would be wise to conform to those wishes. Peter Fraanje, manager NVTB, remarked that use of biobased materials still is a niche market and largely unknown, but Maarten van Hezik, manager STABU, told us that ‘sustainable construction’, subject of an MOU in the sector until recently, now is business-as-usual, and that in a while this will also be true for biobased building. Jaap Messemaker, manager G&S Bouw, said that his firm does not yet do this, but that they investigated the matter.

But the impression remained that everyone is closely watching each other, and that the sector is not eager to get to grips with biobased. Willem Hein Schenk, an architect and chairman to the organization of architects BNA, said that even among clients, there are very few people who know what they want. You would have to convince them of the benefits of biobased. ‘The client expects us to solve that for us.’ Another of his problems: ‘How do we get on board the big guys?’ The audience wondered whether use of biobased products could not be enforced, also for government as a launching customer? But the lack of experience with these materials stand in the way of this. It was good to hear that the audience was of the opinion that we should shift the attention from biofuels to biobased materials. A conclusion wholeheartedly endorsed by the editors of this website.

Green Deals

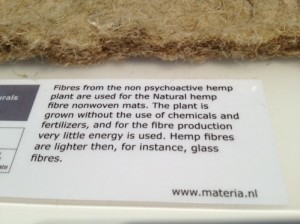

And then regulation, with the official building code as the first hurdle. Its provisions often are to the disadvantage of new materials. For instance, hemp or flax wool is much cheaper and more sustainable than glass wool, but glass wool – provided it is made from recycled glass – has the status of being sustainable. Which hard to fight against.

Roel Bol’s people at the ministry of Economic Affairs have contracted two advisors for this kind of problem. Among them they have contacts with 25 companies which have indicated as issues to be addressed standard setting and certification, the Building Information Model, and Life Cycle Analysis (LCA). Jaap van der Linde and Jan Vloo are independent consultants who investigate which Green Deals the ministry can make with these companies. ‘Swamps from the past, causing a competitive disadvantage for biobased materials,’ they call it. Green Deals can be helpful. So far, the building trade is the only sector where such a concerted action takes place. We will know more by June, this year.

Crisis in the building trade

On the question whether use of biobased materials could alleviate the crisis in the building trade, panelists answered that biobased might be helpful indeed for new innovations. Speakers had already indicated that retrofitting existing houses to an energy neutral standard, using biobased materials, would be a great challenge for the building sector. Surely also because there are hardly any new construction sites left. Someone in the audience remarked: ‘Living in an energy neutral home, retrofitted with biobased materials, is like putting on a woolen sweater instead of a synthetic one, one ‘lives’ much more comfortable in it.’