We are at a turning point in the energy transition, particularly as to the contribution of solar power, says Wim Sinke. So far, the instrument for opening up markets was policy, but it has now become price. Solar panels have become cost-effective for many users. But now, prices have dropped to such an extent that they threaten to break up the chain: some stakeholders cannot make a profit any more.

Wim Sinke is one of the leading figures of solar power in Europe. As a researcher at ECN, he initiated many innovations. A large share of solar cell production worldwide now uses Dutch technology, not in the least thanks to his efforts. Nowadays, Wim mainly works in programming and as a policy advisor.

Excess capacity in solar power

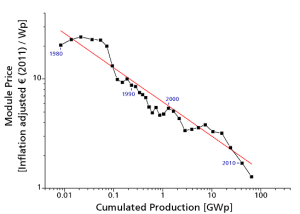

‘Prices of solar panels have come down too fast because of global excess production capacity,’ says Wim Sinke. ‘They are now at the 2020 level, at a normal price reduction trajectory. Fortunately prices fall, for that is a prerequisite for large-scale deployment, but they should not fall so fast that parts of the chain break down. Therefore we now witness a certain stagnation, and we must be careful not to lose valuable elements. If we should follow the historic trend of solar power price reduction (which would imply prices falling less than in the past few years), that would be largely sufficient for success in the future. I do expect lower systems prices in 2020 than those at present (about € 1-2 per Wp), but not twice as low.’

‘So far, prices were the limiting factor in the application of solar power, but now integration of solar power becomes decisive: in the grid, in buildings, in the landscape, in economic models. We still do not have consensus on the ways in which this integration will have to be done. The existing electricity system is huge and deeply rooted, we cannot push that aside and replace it just like that. Solar power will have to conquer its place in that system, and that will involve conflict. Look for instance at the consequences of wind and solar power for the cost-effectiveness of electric power stations. Tragically, on top of that, gas-fired power stations now fight an uphill battle in the energy market, which reinforces coal’s position. In this way, every ton of CO2 emitted less is directly replaced by another one. For the time being, we need fossil fuels, but this outcome is counterproductive.’

The role of Germany in solar power

Over the past ten years, Germany has unmistakably been the driving force behind the global development of solar power. ‘We owe it to Germany that we have come all this way in the development of the PV market,’ says Sinke. ‘Without Germany’s stimulus, we would still be in year 2000 with regards to the development of solar power. And now Germany is the first to run into systems limitations. We can judge from the German example that beyond a solar share of 6% in the electricity market, existing models will have to be revised. The hardware needs repair. And the financial models underpinning them. With this question looming in the background: how will stakeholders be able to make a profit in the future electricity market? Ultimately, relations will be decided by competition in the market, but right now, solutions with which the market comes up are suboptimal and not timely. Soon we will have a huge box of bricks, but what will we be going to construct?

Decentralisation of energy supply

Wim Sinke too is of the opinion that regionalisation and decentralisation are at the heart of the transition towards a sustainable energy supply. ‘That implies a completely new approach to energy supply: bottom-up instead of top-down. At each and every level, at home, regionally, nationally and internationally. Given the opportunity to produce local solar power cheaply, it makes sense to use it locally as much as possible, in order to prevent unnecessary transport. The transition will run through a number of stages. For how long can we manage changes just by smart engineering of the existing system? When do we really have to change to something new? We need new planning tools, like backcasting, from which we will have to identify robust elements for the transition towards a new system. Our present models of the energy market are still incompatible with the quick changes that solar power has brought in the past few years. This has contributed to the present polarisation and stalemate in Germany. The Germans now pioneer for the entire world in the quest for solutions. Ultimately, solutions born from shared interests will be better than those born from confrontation. If interests are shared, solutions can be implemented much faster.’

Wim Sinke is concerned about present developments in the market of solar power. But he looks upon them as growing pains in a process in which the sun will win in the end.