Last week, we could hear everything about the wonderful substance isosorbide, a biobased compound with many useful applications. We were in Lille and its surroundings, on an invitation of the regional development agency of Northern France, and among others visited the company Roquette, a major producer of chemicals derived from wheat and maize starch. Isosorbide for instance, a substance of which they are very proud, and for which they foresee a bright future.

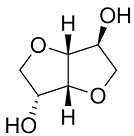

Isosorbide is produced from glucose, the well-known decomposition product of starch, widely used as a sweetener. In a first step, hydrogen is added to glucose, transforming it to sorbitol, another well-known substance, a low-calorie sugar substitute and the agent that makes the ink flow uninterruptedly from our pens. Then, two water molecules are extracted from two sorbitol molecules, producing isosorbide, a substance with miraculous properties. Roquette, who produce isosorbide in moderate quantities from 2002 onwards, has devoted a lot of development work to it; among others, in purification of the impure substance (98% purity, light brownish) to almost complete purity (99.5%, pure white). Roquette developed isosorbide for the production of better polymers, a sector that requires absolute purity of its feedstock. So far, isosorbide had just a few applications in medicine; it is in use as a diuretic and as a cure for heart problems (as isosorbide dinitrate, comparable to nitrobate, the well-known ‘pill underneath the tongue’ for patients with chest pains). So, the health effects of isosorbide are well-known.

Isosorbide offers important improvements

Which polymers does the sector intend to produce from this substance? Firstly, isosorbide can be added to PET (up to ca. 10%), producing PEIT (with the i of isosorbide). The addition of isosorbide produces better heat resistance and better optical clarity to the plastic. Two properties that could be decisive for industry, dependent on the application. An important aspect is that isosorbide does not stand in the way of PET recycling: PEIT is simply absorbed in the recycling process. But Roquette stresses: performance is essential in isosorbide applications, in other words: customers will use the substance because of the good properties of the new plastic, and recycling aspects are absolutely secondary (for the time being).

The second plastic in which isosorbide may play a major role is polycarbonate. This thermoset plastic, used in head lights, household appliances and other applications, is produced so far through the intermediate of bisphenol-A, a carcinogenic substance. Bisphenol-A-free plastics have become a focal point among critical consumer groups. Isosorbide can entirely substitute bisphenol-A in polycarbonate production; this would eradicate this problem, and render polycarbonate food contact applicable. A further advantage of such plastics is that they do not turn yellowish upon ageing, caused by UV light, an important problem. Therefore, the polymer might be a good material for the production of (almost non-breakable) smartphone screens. Mitsubishi Plastics has developed a new plastic on the basis of this new polycarbonate, Durabio, intended for use in the automotive industry and other applications – it can be mixed with pigments and does not need to be painted any more.

The sky is the limit for isosorbide

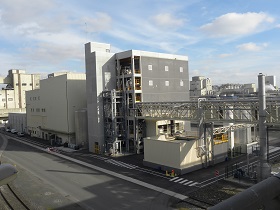

Finally, isosorbide esters can be used as plasticisers, substituting phthalates (suspected of being endocrine-disrupting substances). In total, the three markets mentioned are enormous: several hundreds of thousands tons. Confront that with the size of the new plant, just constructed by Roquette, the most important producer of isosorbide at present: 20 kton – and one might imagine that this French company has hit upon a major source of growth, supposing that isosorbide might be successful in all these markets.

And it does not necessarily stop there. The trend to produce major polymers from biobased feedstock has only just begun. Polyethylene can be produced from biobased ethylene; PET can be produced using biobased ethylene glycol, and using biobased phthalic acid in the near future. And these are just the well-known existing products. Totally new biobased products are in full development, like PEF, a substitute for PET; and, like in the case of PEIT, molecular adaptions of existing polymers through the incorporation of new biobased components. The incorporation of isosorbide is just a first step. We will be going to witness an increasing amount of addition of natural polymers (like sugars, proteins, fats) or their components in our range of polymers. Like in epoxy resins, polyethers, polyamides and even in the majors polyethylene and polypropylene. The issue will be the optimal combination of the old polymers with properties of naturally occurring materials. Which will produce a new family of ‘green’ materials.

Roquette loved to sing the song of praise of the new substance to our group of journalists, but did not answer questions on price or on its plans for further development of polymers using isosorbide, like PUR or epoxy resins. Performance is the driving force, so we bring back to mind – which also means: it is not the price. We surely hope that the latter will not prove to be an obstacle.