‘In agriculture, much diversity has been lost, and as a consequence soils deliver less ecosystem services,’ says Louise Vet. ‘Just recently, we developed the tools to establish this – we can now analyse the DNA profile of soils. We have opened up the black box of the soil, and now discover many new opportunities that do value soil diversity. And we are just at the start of this new development.’

Stability through diversity

Louise Vet is the director of the Netherlands Institute of Ecology (NIOO), an institute of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (KNAW), and professor of Evolutionary Ecology at Wageningen University. Her own area of expertise is plant ecology, herbivorous insects and their natural enemies like parasitoid wasps. Her research already showed her the importance of messages sent by plants to their enemies and the enemies of their enemies; as our knowledge of soils now expands rapidly, she can see many more connections between subsoil and aboveground life. For instance, NIOO researchers found that subsoil and aboveground insects can communicate through a plant. In this way, they use the plant as a kind of telephone. If subsoil insects eat from the plant, the leafs send signals. Aboveground insects then rather choose another plant, in order to prevent competition and above all in order to evade the plant’s toxic defence substances. NIOO researcher Olga Kostenko even discovered that the soil files messages as insects eat into plants. Future plants at the same spot record that message and transmit it. Such signals are very specific: in this way, the new plant can transmit the old plant’s trouble with aboveground insects. In short, the plant not just acts as a telephone but even leaves behind subsoil voicemails.

Because we have put such a one-sided emphasis on fertiliser and on production maximisation, says Louis Vet, we have neglected life in the soil way too much. Because of this, some 20% of global agricultural land has degraded. Worldwide, soil organic matter content, the microbacterial feed, decreases. The same holds true for micronutrients, that receive much less attention than they deserve. As we can now witness what goes on in soils, we discover the enormous diversity of soil life. The soil microbiome exactly parallels the human gut microbiome: it fulfils many functions, of which we discovered just a tiny bit so far. This microbiome feeds the plants, it can protect them from draught and other exceptional conditions, and fulfils an important function in protecting them from diseases. It is a system in the full sense of the word, in other words it provides stability and resilience – shock resistance. A property that may be of great importance to agriculture. Louise gives the example of the research of NIOO researcher Maarten Schrama on maize yields in Vredepeel in 2013. This was an exceptionally dry year; and remarkably, conventional maize growers suffered much more than organic growers: in this year, organic yields surpassed conventional yields. Apparently, the diversity of the soil system provided adequate protection from draught stress. Conventional agriculture should start making much more use of such system services, Louise says. That would require a reappraisal of soil diversity – in other words, conventional agriculture should distance itself from the restrictive NPK approach with chemical pesticides use, and evolve towards a systems approach.

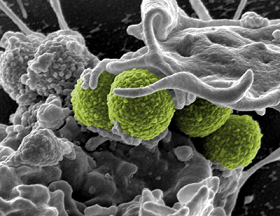

Microbiome

Many agricultural companies now have discovered the microbiome, including majors like Syngenta, Bayer and Monsanto. They acknowledge that chemical crop protection approaches its limits and spend much money on microbiological research. But new reductionistic approaches always lie in wait: looking for the one magical agent that would have super effects, whereas we know on beforehand that only symbiotic communities of yeasts and bacteria deliver the required ecosystem services. For instance, researchers at NIOO discovered that soil bacteria and yeasts communicate a lot through ‘volatiles’. A close link has been established between these substances and plant resistance to diseases and plagues. Soil biodiversity offers new opportunities to reduce pesticide use. NIOO researcher Martijn Bezemer now researches this for chrysanthemum growing – an agricultural branch that always involved much use of pesticides.

Louise Vet imagines a new agriculture developing along these lines, eventually causing much less environmental damage. Conventional agriculture will be able to approach organic agriculture. By working with nature instead of opposing it, with more attention for biological diversity: restoring the use of local varieties, and the reappraisal and use of landscape design, with hedges, earth walls and differences in land use intensities. In order to allow agriculture to feed the world in a healthy ecosystem.