Last week, we wrote about the versatile and biodegradable plastic PHA. The Dutch Platform Agro-Chemistry-Paper reacted to it: could you also highlight the pitfalls? Do you recognise the danger that most Dutch PHA projects start from waste as a feedstock, whereas there is no market demand for a product with such a background? In other words: how shaky is the PHA business case?

Policy as the driver behind the PHA business case

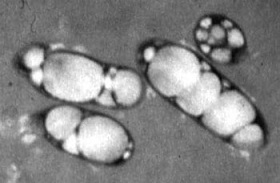

PHAs have a history with more failures than successes. The compound’s properties (perfectly biodegradable), and its production process (directly from bacteria, not in a chemical reactor) capture the imagination – but so far, that does not generate any market demand. The product’s price is too high. Many entrepreneurs in (subsidised) projects assume that authorities will over time require biodegradability from many plastics, and that this will generate demand for PHAs. Which would make the PHA business case look better.

But if the PHA has been produced by bacteria from waste, market demand may never take off. The only successful PHA projects right now (those of Newlight Technologies and Mango Materials) use methane as the feedstock. In other words: their product can be processed to pure PHA specialties and will not be contaminated with heavy metals, remains of infectious organisms and the like. Projects that produce the compound from waste cannot offer such an assurance. Even less so if the waste in question has no clearly defined composition, like from waste water treatment facilities. Although PHAs make good food packaging materials, PHAs from such sources might be banned by health regulation – and even if they would be allowed, producers or consumers might boycott such a product. These restrictions might be less severe if the PHA were used as a biodegradable agricultural plastic – but that remains to be seen.

Preparing for the circular economy

But the PHA business case might suddenly look much brighter if the product were made from well-defined waste streams, in particular if the company that produces the waste would embark on PHA production. The chocolate processing factory or the paper mill, companies who know exactly what their wastewater contains, might use this for production of PHA, that they can subsequently use for packaging or coating purposes. From a regulatory point of view, the wastewater would then not even qualify as waste – very important, because once a side stream qualifies as a waste, its processing will have to comply to very strict health regulations. And producers could do even better, if in conceiving their production process they would take into account straight away their waste’s quality and the extent to which it can be processed further. As soon as a food processing industry for instance discharges its proteins, these become valueless, whereas they keep a certain value within the confines of the factory gate. Therefore, resources should be reprocessed as early as possible in the production chain. That is preparing for the circular economy! Do not wait until the side product ends up in an undefined waste stream. Moreover, it is impossible to produce PHA specialty products from impure waste streams with varying contents. Even if researchers should come up with technological solutions to this problem, these would further add to production costs.

In other words, the PHA business case does not depend solely on the quality of the process and of the product, but also on the quality of the feedstock and the costs of processing. Entrepreneurs wishing to enter the PHA market should ask themselves once more: why would customers be inclined to buy my product? And does my brand of PHA really perform better than competing plastics?