In 1971 I did a work placement at Tel Aviv University in Israel. It was a wonderful and decisive period in my life. The researchers in the lab judged it more important that I got to know their country, than that I did some research for them. Saturday, Sabbath, was their only day off, but I was allowed to travel on Friday afternoon, and was required to be back only Monday morning. With both hands, I seized the opportunity. Several times I stayed overnight in a kibbutz. The youngest and poorest that I visited impressed me most. There I saw what well-being for all is all about.

Hans Tramper is professor emeritus in Bioprocess Technology at Wageningen University and reflects on the development of his subject in a series of essays. His pieces were published so far on 18 June, 30 June, 11 July, 22 July, 19 August , 10 September and 21 September 2018.

One Friday, I arrived there by the end of the day; they had already reached the maximum number of visitors, but still improvised a place for me to stay. A nice woman showed me around and told me about life out there. Their main goal was to cultivate an area of the desert large enough for them to live off the land with their community in well-being. All members of the community had been assigned a task of their own, and did whatever they were good at. Even school children were stimulated to develop their talents from the early age onwards. Everything was small, efficient, effective and spotless. They barely had any machinery and devices. The food served was produced by themselves, farm-fresh, diverse and prepared on the spot. Simple and tasty. The atmosphere was gay and stimulating. Unified in the common goal: well-being for all. I would have loved to stay there.

Millennium goals

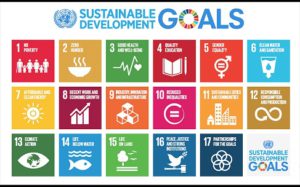

In 2000, the UN formulated eight development goals with 2015 as their deadline. These Millennium goals intended to reduce poverty in the world; they were not a complete failure, but still required a firm update by the end. In December 2014, the document The Road to Dignity by 2030 was published, that contained seventeen new development goals. It contained secretary-general Ban-Ki-moon’s vision, and was completed through four years work and many rounds of participation. They were finalized in December 2015 at the Global Climate Conference in Paris. The seventeen new sustainable goals for 2030 take it a step further than the preceding ones; they address problems that concern the entire global community: climate, safety, human rights and global improvement in wealth. These goals run parallel to the transition that I have in mind, the difference being that I prefer not to speak about global improvement in wealth, but about well-being for all, well-being meaning the experience of satisfaction in one’s own conditions of life.

The Earth, our primal mother

The Earth, our primal mother

Viewed from outer space, planet Earth is less than a minuscule pin-head, even viewed from the nearest star, our sun, an average star, but still an ample source of energy for the earth, the source that makes life on earth possible. Viewed from the human perspective, the earth was almost infinitely large, flat and the centre of the universe, just a few centuries ago. The extremely fast technological advancements of the past few decades have turned the earth into a Global Village, where the different cultures and societies, less than a century ago almost isolated from each other, now mix and clash more intensively all the time. Once infinite and flat, the primal mother Earth has ‘degenerated’ into a small spherical planet, a breeding ground in which completely different cultures will have to bloom to communities in which each person feels at ease.

All human beings are unequal

This is the title of a book (1994), written by professor emeritus and geneticist Hans Galjaard. The differences between human beings are not just caused by their genetic makeup (Nature). To a considerable extent, they also arise from the different environments, cultures, in which human beings grow up; therefore, they are also Nurture, partly determined epigenetically. There are major differences between cultures, religions, peoples, people themselves. Even on the level of DNA, so researchers discovered recently, differences between individuals are more important than they thought. So, all human beings are unequal. And still, we have to try to survive as a species without decimating each other through wars. I am convinced that we can do this, because I judge the differences among people of the same race to be more important than the average differences between races, cultures, religions etc., meaning that these will not stand in the way of living together. There are plenty of local examples of this.

‘Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world’ (Nelson Mandela).

If we should wish to turn the earth into a Global Village, in which different societies and cultures live together peacefully, with an eye on good stewardship for our planet, then it may become the breeding ground for well-being for all. In order to arrive there, we need more technological innovation and dedicated policies. We will have to agree on that first of all. If we all should prioritize this, then technological developments could move very fast indeed, they are moving fast already. Gene technology could play an important role in the necessary changes, as we will argue later in this series. What matters most now is to take a positive attitude towards it. What should we do? First of all, start discussions on it. This is the most important reason for me to write this series: to stimulate this, by writing in an uninhibited way about the multitude of opportunities in gene technology. Ideally, the governments of some prominent countries would organize major discussions on a global scale. That first of all, and, of course, also extra funding for the development of new technologies. In order to turn the earth into a breeding ground of well-being for all. Ideally, a world with a balanced distribution of well-being, i.e. enough and healthy food for everyone, sustainable energy, housing, tailor-made education and health care, and care for each other. Finally, all human beings are unequal… and this way we should keep it!

Breeding ground of well-being for all

But how should we go about this, how could we turn a world dominated by selfish genes (i.e. greed and lust for power) into a world-wide social community where mutual care and satisfaction are the standard? Which genes would be responsible for those conditions, and how would one get those genes genetically in the right form, or reset them epigenetically (back) to the appropriate position? In later essays on tailor-made health and well-being, I will return to this. Any changes should always be brought about voluntarily; we should refrain from pressure and coercion. We should rely primarily on individual choice, good education and safety guarantees. I have in mind the school children in the abovementioned kibbutz that were motivated to develop their talents. Which hormones are responsible for the feeling of well-being? How are they regulated, directed? How does that happen in living cells? In our brains? We do not have proper answers to such questions, yet. Using gene technology, we could generate at an increasing pace answers to these questions. And do something with them! What would that entail? It would mean that the target of modifying genes for therapeutic purposes would become clearer. As a matter of fact, researchers experiment on genetic therapies for mono-genetic diseases for twenty years already, albeit unsuccessfully at times. The promotion of global health with a better distribution of well-being in mind, could become a new goal. But I need to stress again that we should secure individual freedom, good education and safety guarantees. Therefore, I finally repeat my last sentence of Essay 1: ‘The essential question is, how long it will take us to dare tackling the political taboo that surrounds genetic technology, without drowning in the old morass of the classical eugenics.’