In September 2017, the FAO released a report on hunger in the world. According to this report, in 2016 11% of the global population experienced hunger, i.e. 815 million people, 38 million more than in the preceding year. This is rather shocking, as the rise comes after a gradual decline in the preceding decade. All the more so because it affects 155 million children under the age of 5. Causes for this, according to the FAO, are climate changes, slower economic growth causing less food security, and in particular serious conflicts in a number of areas around the world.

Hans Tramper is professor emeritus in Bioprocess Technology at Wageningen University and reflects on the development of his subject in a series of essays. His pieces were published so far on 18 June, 30 June, 11 July, 22 July, 19 August , 10 September, 21 September and 30 September 2018.

Millennium goals and hunger

The FAO (Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations) report is the first global UN review of food and food safety after the approval of the seventeen new UN sustainable development goals, decided upon in December 2015 during the Global Climate Summit in Paris (see Essay 1 and Essay 3 part 3). Zero hunger and malnourishment before 2030 is one of the international top policy priorities; in 2030 these second Millennium Goals expire. In a special report, the FAO investigates how in 2050, mankind can avoid hunger and sustainably produce food for the expected population of almost 10 billion people. According to the FAO, a business-as-usual approach will be insufficient, particularly in view of climate change and other forces (‘planetary boundaries’) that threaten our natural resources (see Essay 3 part 2). Keep in mind resources like biodiversity, available land and pure (fresh) water, each of them essential for food production, agriculture, forestry and fishery. We need to apply conventional technologies, and in addition to them strongly stimulate new innovative technologies such as precision technology, gene technology and modern biotechnology in general, in order to cope with these challenges.

Genetically modified crops

Genetically modified crops

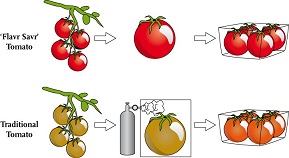

May 18, 1994, the American FDA declared the transgene tomato ‘Flavr Savr’ produced by Calgene to be as safe as a common tomato. This amounted to the breakthrough of the first commercial food product produced through recombinant-DNA technology. By adding an extra bit of DNA, Flavr Savr has been genetically modified in such a way that a certain gene is not expressed, meaning that the protein for which this gene codes is not produced by the cell – we call this antisense technology. The protein in question is polygalacturonase (PG), an enzyme that speeds up the rotting process. PG breaks down the pectin in cell walls, causing the tomatoes to weaken and rot faster. By means of this genetic change, the tomato can be stored at least ten days longer. It also allows tomatoes to ripen and redden on the plant. Most common supermarket tomatoes are being picked while still green, and then treated with ethylene gas (particularly in the US) to develop their red colour, which treatment leaves insufficient time for all flavourings to develop. Therefore, Flavr Savr, as its name already suggests, is a tastier tomato with clear benefits to the customer. Remarkably enough, there was almost no public resistance against this genetically modified crop. In 1995, Calgene was also granted the right to sell Fravr Savr in Canada and Mexico. Under the name MacGregor, the tomato was sold in some 3,000 shops for a number of years, after which it was taken off the market because it did not earn enough. In her book First fruit. The creation of the Flavr Savr tomato and the birth of biotech food (McGraw-Hill Education, 2002), Belinda Martineau tells all there is to know about Flavr Savr; she is one of the Calgene researchers that developed this kind of tomato.

Since the introduction of Flavr Savr, the area cultivated with transgene crops grows appreciably each year in many countries, but not in the EU, for there they have been banned for a long time already. The four most important transgene crops at present are: soy, maize, rapeseed and cotton. Recent meta analyses show that transgene agriculture produces safe products, environmentally benign, and hence responsible, both economically and ethically. And yet, plant gene technology has been criticized for decades. Anti-organizations like Greenpeace and Friends of the Earth exploit masterfully the lay-people’s fear for super weeds, cross-breeding etc., with the effect that genetically modified crops are almost completely banned in Europe. Farmers across the world are unhappy with this state of affairs, as mega research shows that transgene crops and food are safe and economically sound, even stronger, that it would be ethically irresponsible to ban them.

Fusions/Mergers

May 21, 1997, Calgene was taken over by the American gene tech company Monsanto, a development that I looked upon with sorrow. The announcement last year September of the coming merger of the German chemical giant Bayer with Monsanto, hated by many by now, even worried me a lot. By now it may be clear that I am a proponent of gene technology. A fierce proponent, according to the anti-gene tech movements; but I tend to agree ever more with one of their objections. The power over seed, new varieties and pesticides, meaning over the entire food chain, now comes into the hands of a very small number of multinationals. There were few such companies a few years ago, but now only three remain! After three major mergers/takeovers: Dow and Dupont in 2017, ChemChina and Syngenta (since October 2017, ChemChina owns more than 98% of Syngenta shares), and so now, since 16 August 2018 definitely, Bayer and Monsanto too. On the web page containing this announcement, they also say, rather hypocritical in my view: ‘Today’s milestone means that the two leading innovators in agriculture will now come together as one to shape agriculture through breakthrough innovation for the benefit of farmers, consumers and our planet.’ I still judge this to be a worrying, even alarming development.

Doesn’t the Netherlands play a part in this? No! Who will control these giants? Governments? That was not, and is not to be expected. After the presidential change in the world’s most powerful nation I got really worried about this upcoming takeover, and since February 6 this year I even got scared, as what I read in Business Insider that day made my hair stand on end. Mid-January, the two top dogs of Bayer and Monsanto appeared to have had a ‘productive’ chat in the Trump tower with its top dog, who is very much in favour of their megalomaniacal plans. On January 17, the Dutch business newspaper FD wrote an article headed ‘Bayer and Monsanto too, buckle under Trump’, indicating that this combination will spend half of its research budget in the US, and will create several thousands of well-paid jobs with these funds.

Will this please the American farmers? I guess not. Most of them expect prices for seed and pesticides to rise, and then smallholder family farmers will surely run into difficulties. Enquiries by their Farmers Business Network do indeed show enhanced market power to correlate with higher prices for seed and pesticides. That will not please any farmer. All in all, I am not the only person who is concerned.

Experimental applications

The abovementioned FAO report shows that of the 815 million people having hunger, 520 million live in Asia, 243 million in Africa and 42 million in Latin America and the Caribbean. Bangladesh is such a country tormented by hunger and disasters. In 2014, its government approved the experimental application of genetically modified eggplants and twenty smallholder farmers started growing them. Now, four years later, they number over 27,000. In the next part of this essay, this so-far-successful story.

Interesting? Then also read:

Genetically modified food

Genetic engineering serves sustainability

Breeders’ rights, patents and genetic modification