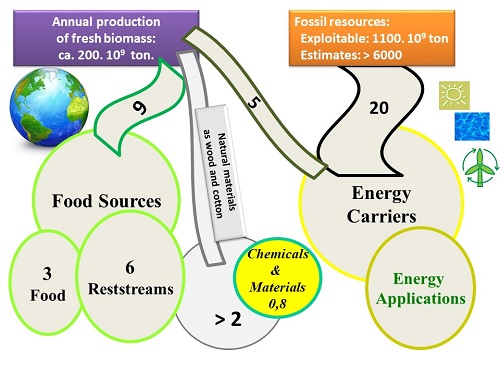

Why cannot we lift all barriers for the use of bioenergy? Because the energy sector is much larger than the food sector. The 20 billion tons of fossil fuels that mankind uses each year, is equivalent to 40 billion tons of biomass; whereas our yearly harvest for food is 9 billion tons, of which 3 billion tons will eventually end up on the plate. Bioenergy will sooner or later cause an imbalance if given free reign.

This is the second of two articles on limits to the use of biomass for energy purposes. The articles were published on 5 October and 23 October 2018.

Bioenergy needs water and fertilizer

Releasing biomass for energy production would be equivalent to allowing five hungry eaters to a table lain for one (for: 45 billion tons of demand for bioenergy compared to 9 billion tons for food production). Of course, those five will happily make use of the existing infrastructure for production of, and trade in food: markets, distributive trades, transport, processing. Which is likely to increase chances of harmful competition. And then, these five will have a thirst for water; no biomass production without water, and in many places on earth, (clean) water is even a bigger problem than energy. But the picture looks entirely different if we would not produce energy from biomass, but materials: bioplastics.

Biomass lends itself quite well for the production of useful materials. This requires precision, opposite to the use of biomass for energy: finding precise applications for each component of the biomass. And this requires substantially less biomass than needed for the production of bioenergy. The production of all polymers in the world falls far short of one billion tons per year; in principle, this amount could amply be produced from the annual agricultural side streams. For this reason, people like the Groningen professor in environmental sciences Ton Schoot Uiterkamp judge that we should only produce energy from biomass if all other options have been depleted. For instance, if we produce the bioplastic PLA (polylactate) from sugar, we are still left with many side streams of the sugar beet: leaves, roots, pulp. It would be quite possible to retrieve pectin and proteins from them. But finally, we will be left with a residue for which the best means of processing is to feed it to a fermentation unit to produce biogas: bioenergy. Like Schoot Uiterkamp says: ‘Biomass sounds good. But should we therefore use it for energy? In don’t think so. Remember for instance that we need a worrying amount of water and minerals already for the production of many crops. The water footprint of many crops is terrible. Like cotton. And that would get worse if we should use those crops for bioenergy production. Like miscanthus, a crop that needs much water but is looked upon by many as a very good energy crop. And eucalyptus, of which entire woods have been planted in Southern Europe, even with EU subsidies, in order to produce bioenergy from it. Those trees retrieve their water from very deep and totally dehydrate their environment – why would we witness so many persistent and large-scale forest fires nowadays? Biomass-for-energy is fine as an option of last resort, after we have taken all useful components out of it.

Unexpected consequences

This, says Schoot Uiterkamp, is an example of our lack of thinking in complete systems. Many people, among them most policy makers, only take a view on part of reality and do not oversee the effects of policy measures on other areas. Like in the case of biomass: we need to control CO2 emissions, biomass seems to be fit for the job, let’s just do it. At the turn of the century, policy makers initiated this course on a large scale. This resulted in the creation of an entirely new economic branch. Biomass is not just for the production of biofuels; burning wood pellets as co-firing in coal fired power stations constitutes a form of bioenergy as well. That is fine and well as long as the wood comes from marginal forests with no other application; but by the time an entire new economic sector has come to life, those wood pellets become an excuse to keep coal fired power stations going – exactly the opposite of the intended effect. And early this century so much biomass (easy biomass: maize) was used for the production of biofuels, that maize shortages appeared. In Mexico in 2008, that led to uprisings, the so-called taco crisis: tacos became too expensive for ordinary Mexicans to be able to buy them – for the maize went into the tanks of American cars. And in Egypt too, people took to the streets, because wheat had become so expensive. The competition between biofuels and food is real!

We need to uphold three principles in order to secure quality of life on earth, says Ton Schoot Uiterkamp. First: as far as we use non-renewable resources, we should use these for constructing renewable systems. I.e. fossil fuels not for heating our homes and driving our cars, but for development and application of solar and wind energy. The second principle repeats Von Carlowitz’s eighteenth century insight: we should not use natural resources too fast; they should be able to restore themselves. Think ground water, fish, forests. All of them ‘resources’ that mankind is in danger of depleting by harvesting too much of them. The third principle is that we should not transgress ecological boundaries, in order to allow the earth’s system to restore itself. For instance only emit waste water clean enough to allow fish a healthy life. And restrict CO2 emissions to amounts that system ‘earth’ can still manage. These principles were first formulated by environmental economist Herman Daly. Obviously, mankind does not respect them most of the time.

Bioenergy is inefficient

In an ideal world we might very well use biomass within these limits for energy production. But we should then be very careful not to stretch those limits. Neither should we expect biomass to solve our energy problem. If we should use biomass in a responsible way, it will contribute a modest share to sustainable energy production, say 5%. But last decades’ events show us that opening up the biomass tap will quickly have irresponsible consequences: competition with food supply, burning down tropical rain forests, use of precious water just for energy production. Like Ton Schoot Uiterkamp says, bioenergy is for the end of the road: as there are no other useful applications of the resource. And yet another factor: biomass is a very inefficient way to put good use to solar energy. Many modern solar panels can transform 20% of incident sunlight into energy, and quite higher efficiencies are in the offing. The most productive crops, like sugar cane and sugar beet, score 1½%. We would therefore use thirteen times as much land in order to harvest the same amount of energy. Even if we should now plant energy crops on a major scale, the next generation will judge this to be a waste of land, and cover it with solar panels. Even underneath those panels we can still harvest biomass, like vegetables that grow best in the shadow.

And yet, using biomass for energy remains a good idea – at the end of the road, when we have no more useful applications for the resource. So materials first; the amount of energy that we can harvest from biomass will primarily be determined by the ‘side streams’: from agriculture, and from materials production.

Interesting? Then also read:

Still a one-sided emphasis on the energetic use of biomass

Respectful treatment of the complexity of biomass

Biobased economy strategy: through specialty chemicals and materials