Since the turn of the century, there is a discussion raging on the limits to biomass use for energy purposes, in order to control man-made CO2 emissions. After having been greeted with enthusiasm at first, bioenergy is now met with many more restrictions. How do we look upon this after all these years?

This is the first of two articles on limits to the use of biomass for energy purposes. The articles were published on 5 October and 23 October 2018.

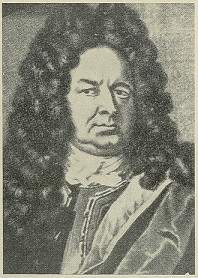

Would thinking about sustainability have originated just recently? Kindled for instance by Rachel Carson’s book Silent Spring in 1962? No, the founder of our thinking on sustainability lived much earlier, around 1700. He was a German nobleman, with the name Hans Carl von Carlowitz, a descendant of a family of stewards. He is famous in Germany but almost unknown elsewhere. His area in Saxony, the Ore Mountains, were rich in silver ore. But by the end of the 17th century, the silver mines, that employed a major workforce, were threatened in their existence. The problem was not that the ore was depleted – the problem was that the wood that served to support the mine galleries was depleted. Wood was also used for making charcoal, that served to melt the ore. For silver mining, major forests were cut down for many decades, without proper re-establishment. Brooks were canalized in order for wood to be transported from further away, but that just postponed the crisis and did not prevent it. Because of disregard of limits to biomass use, some mines had to close down because an essential tool was no longer available.

Sustainability, already in the 18th century

In his book Sylvicultura oeconomica, oder haußwirthliche Nachricht und Naturmäßige Anweisung zur wilden Baum-Zucht, Von Carlowitz formulates rules for mankind to treat a scarce resource like wood. We need to replant trees, he says, at such a pace that the growth will equal the logging. ‘In these countries, the highest level of art/science/diligence is dependant / on such conservation and planting of wood / that this results in a continuous and sustainable utilization / because this is a prerequisite / for the survival of the country’ (p.105-106). This is long before the Limits to Growth report! The essence is in the words ‘sustainable utilization’, in German ‘nachhaltende Nutzung’. In the seventies of the twentieth century, the German Greens revived Von Carlowitz; consequently, the German word for sustainability is ‘Nachhaltigkeit’, continuability so to speak.

But this continuability is far gone if mankind would set aside precision and would disregard limits to biomass use with the goal of reducing CO2 emissions. This may look great if we just take into consideration the big picture and omit the details. Each year, our planet produces about 200 billion tons of biomass. Some 9 billion we need for food production; in the end we consume 3 billion tons annually, so superficially there would be ample room for some energy production. But that perspective changes drastically if we express global annual energy use in biomass: that would amount to 45 billion tons, five times as much as we grow for our food. At present, we burn 4 billion tons of biomass, mainly wood, straw and manure (in particular in simple use in developing countries); we would have to use the remaining 40 billion tons for the same amount of energy production as is now delivered by fossil fuels (2 tons of biomass roughly equals 1 ton of fossil fuel).

The controversy on limits to biomass use

There is much disagreement on the question whether we need to use biomass for energy production. Around year 2000, biomass was the favourite idea of climate activists and policy makers. At that time, they welcomed almost any idea on sustainable energy. We did not have a clear eye yet on the potential of solar, wind and water energy, and other sources. It was early days for real choices. Biomass was a readily accessible alternative, as we could move on quickly, making use of the scale, infrastructure and long experience of food production and trade. It might have been obvious then already that mankind would preferably use food ingredients for the sake of convenience (sugar, maize, palm oil), but that objection was brushed aside. Proponents used to say that we could grow fast growing crops on unused lands. So-called marginal lands: prairies, pampas, savannas and poor meadows. But in 2008, Tim Searchinger, professor at Princeton University, and others published a controversial article in Science; with the telling title ‘Use of U.S. Croplands for Biofuels Increases Greenhouse Gases Through Emissions from Land-Use Change’. The discussion that he sparked continues until today. Look, Searchinger said, if you just consider growing the crop, for instance maize, then the result will indeed be a reduction of CO2 emissions by fossil fuels. For the CO2 emitted at incinerating the biofuel has been captured beforehand by the growing crop; pluses and minuses add up to zero (if we disregard diesel oil for tractors and energy used in fertilizer production). But then you forget, he says, that this maize cannot be eaten anymore, and needs to be grown elsewhere on new land. For instance on a prairie. But the prairie’s soil contains much carbon containing humus, of which a large part will be oxidized to CO2 on tilling the land. So what’s the gain? This is called the effect of Land Use Change, LUC.

But matters can become worse. Growing maize in the US may substitute growing soy. Subsidized fuel, isn’t it, soy cannot beat that. Another possibility: policy dictates a mandatory content of biofuel in the fuel mix, then the demand for maize also increases; extra costs of biofuel production will be carried by the consumer, not by the tax payer. Other system, same result, just a shifting of funds. In both cases, soy is being substituted by maize. But there still is demand for soy, so in Brazil they enlarge the area planted with soy. Often to the detriment of forests in the Amazon area. In the end, the biofuels used in the US cause burning down large areas of virgin forest, in order to turn them into soy plantations. This is Indirect Land Use Change, ILUC. In the end, Searchinger says, the result is negative. If we do not impose limits to biomass use, we do not reduce CO2 emissions, we waste subsidies, and we destroy the Amazon forest.

People are lazy

In actual practice, there is yet another problem attached to biofuels: the easiest biofuels come first – to the detriment of food production, and (again) tropical forests. The easiest way to produce bioethanol is from sugar or wheat – food ingredients. For biodiesel we need vegetal oils, like palm oil (a food ingredient as well), for the production of which major areas are burned down in tropical forests (again), in Indonesia and Malaysia. Even if we disregard the fate of the orang-utan and the choking smoke that covers much of the area, including Singapore, part of the year, this is not what we were looking for when we started driving our cars on biofuel. But it is hard to prevent such practices. With regards to Indonesia: we do not know if Western public opinion is considered at all there; and there is still much criticism on international traders in palm oil, who cannot track the origin of their product. It is difficult to counteract such practices from Western headquarters and capitals; time and again traders search and find the line of least resistance. Since 2008 however, there have been major adaptations in policy, like the promotion of ‘second generation’ biofuels (made from straw and other non-food resources) over the ‘first generation’ (made from food ingredients).

In the next article, we will look into practicable limits to biomass use and an acceptable biofuels policy.

Interesting? Then also read:

What is biomass anyway?

Still a one-sided emphasis on the energetic use of biomass

Better biomass utilisation in the biobased economy