Researchers do not apply genetic modification just to microorganisms and plants. Animals are genetically modified as well, we will treat this in the articles of Essay 5. With regards to plants, the entire process of regulation and acceptation is complicated and lengthy; with regards to animals it is like a never-ending story. After thirty years, the genetically modified AquAdvantage GM salmon is for sale on the market, finally, but that does not mean that this first animal GM food has been generally accepted.

In the Netherlands we have the transgenic bull Herman as an example of such a never-ending story. Right from its birth in the early ‘90s it has been in the spotlight, and much discussed. Now its mounted remains are on display in the Naturalis museum in Leiden. The exciting story of his its life can be found on Wikipedia.

Hans Tramper is professor emeritus in Bioprocess Technology at Wageningen University and reflects on the development of his subject in a series of essays. His pieces were published so far on 18 June, 30 June, 11 July, 22 July, 19 August , 10 September, 21 September, 30 September, 10 October, 31 October, 8 November, 2 December and 26 December 2018, and 21 April, 28 May and 26 August 2019.

Why genetically modified animals?

Animals are genetically modified for the following practical reasons:

(1) In order to ‘improve’ domesticated animals and fish

(2) In order to retrieve high-quality (humane) proteins from them, medicines in particular

(3) In order to produce organs from them for xenotransplantation, the transfer of animal organs to human beings

(4) In order to produce better test animals

(5) In order to control harmful insects and other vermin.

In Essay 5 I will dwell upon each category and show at least one example. In the first part, we will look into the development of GM salmon. It is the first transgenic animal ever approved for human consumption.

AquAdvantage salmon

I treated this subject for the first time in my book Modern Biotechnology: Panacea or new Pandora’s box? (2011). I repeat this here, in a slightly different wording. ‘The AquAdvantage salmon has been bred by introducing into the Atlantic salmon a growth hormone gene from the chinook salmon, surrounded by promotor and terminator regions of the anti-freeze gene of the ocean pout. Through these modifications, the GM salmon grows twice as fast. But that it will end up six times as large as the ordinary salmon is an urban legend, it will end up the same size. The most important advantage for fish farmers is that the AquAdvantage salmon will grow even in cold conditions. Therefore these salmons reach their ‘market weight’ earlier. They also need less food in order to arrive at this weight. AquaBounty Technologies, the producers, expect this GM salmon to come to the market in 2011.’ This was the rather optimistic information then available.

GM salmon: it will refresh you!

The Dutch newsletter C2W Life Sciences, 28 April 2012, published my column GM fish on your plate: savoury and healthy! Early 2014, at the occasion of my retirement, I rewrote this into a more topical version for my book Gene Whispering: Art and Science, a collection of fifty columns on gene technology. In the column at hand, GM salmon: it will refresh you! I write, in a shortened version:

‘Depressed? Bad eyesight? Eat a fatty salmon more often and you will view the world through a rosy lens again. But will that also be true if you put GM salmon on your plate regularly? The FDA say so. At least, as long as it is AquAdvantage salmon. In October 2011 the FDA declared this GM salmon to be fit for human consumption. But now, early 2014, it still ploughs through a mountain of thirty thousand objections. Again, this year (ever since 2010), they expect this GM salmon really to come to the market. […] The American gene technology company AquaBounty Technologies, the producers, have been preparing market introduction ever since 1995 and have excluded all sorts of risks, in consultation with the FDA. […] The company took these precautions in order to take the wind out of the sails of anti GM activists. […] The gentech company relies on public opinion to judge that these precautions guarantee a safe and profitable production of a very healthy and protein rich food, that contains a high concentration of omega-3 fatty acids as a bonus. […] It now waits for the final go-ahead of the FDA and the ultimate blessing from Washington.’

Since 2014 a lot has happened, but the story has not ended yet.

The never-ending story

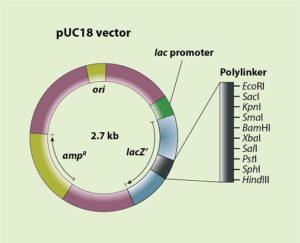

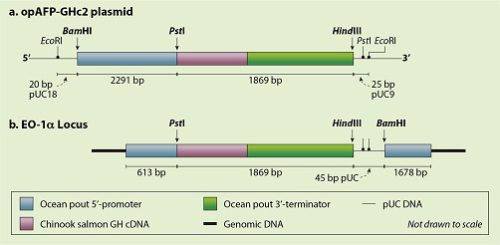

In the beginning, A.D.1989, researchers of the Memorial University in Newfoundland, Canada, lay the foundation for research and development of a GM salmon by producing the AquAdvantage gene construct. This gene construct (compare the Arctic Apple gene construct in Essay 4.7) is incorporated in the pUC18 vector (Figure 1). But in producing the various intermediates for this construct, they also use three similar bacterial plasmids (pUC9, pUC13 en pUC14) – this detail is important for the FDA regulatory procedure. These plasmids have been grown and isolated from the E. coli K12 strain DH5α; E. coli K12 is a much-used bacterium in the lab, also applied in the production of chymosin (rennet enzyme) and looked upon by FDA as GRAS (generally regarded as safe). The researchers use standard techniques of molecular biology like selectively cutting plasmids with specific restriction enzymes (endonucleases) and reconnecting the new loose ends using DNA ligases. Such a multi-step synthesis was much used at the time. The final construct contains the cDNA (GHc2) of the growth hormone of the chinook salmon. Its expression is regulated by promotor and terminator regions of the antifreeze-protein gene (AFP) of the ocean pout. They code this ‘all fish’ gene construct as opAFP-GHc2 (Figure 2a). On the basis of information released by the company to the FDA, these come to the conclusion that the gene construct nor intermediary constructs contain any coding sequences that could have been derived from known toxins, pathogens, oncogenes and/or tumour suppressing genes. Neither do they contain sequences derived from transposable elements or retroviruses that might cause the construct to move around, which could have possibly unforeseeable consequences if that should happen.

Figure 2b the gene construct as it has been introduced into the salmon genome; (upstream) 5’à 3’ (downstream) is the direction in which the coding strain is read upon translation to mRNA. Adapted version of the figure in Science Response 2013/023.

That very same year, 1989, the researchers inject this construct into fertilized eggs of a wild Atlantic salmon. First they cut open the plasmid on both sides of the gene construct, using the restriction endonuclease EcoRI (Figure 2a), followed by phenol/chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. They then dissolve the precipitate, containing the linearized plasmid fragment and the released gene construct having small remaining bits of pUC18 (20 bp) on the left-hand side and pUC9 (25bp) on the right-hand side, in a sterile physiological salt solution (0.9% NaCl in water). They then inject a dose of 2-3 nL into the fertilized eggs. They select the ‘ancestor’ of the AquAdvantageâ salmons from the first generation of the breed in 1992, christened EO-1. Never do the researchers come across the plasmid fragment, not in the first nor in consecutive generations (apart from the two side fragments); they also looked in vain for (fragments of) the ampicillin resistance gene. Therefore, the FDA comes to the conclusion that these fragments are not contained in the GM salmons and that they can disregard this issue in the consecutive steps of the regulatory procedure. The production cycle of this GM salmon is 16-18 months, half of that of the wild ‘ancestor’ (Schipani, 2016).

At first the researchers find new pieces of DNA on two locations in EO-1 and they call them α- and β-integrants. Only the α-integrant appears to speed up growth and by selective breeding they manage to get rid of the β-integrant. At first they crossbreed EO-1 with wild salmons from the Canadian provinces of Newfoundland and Labrador, but since 2000 primarily with a domesticated variety originally from the St. John River (province New Brunswick). The present AquAdvantage salmon therefore is a domesticated transgene Atlantic salmon variety. The location of the gene construct in the genome is important for the proper functioning of the authentic genes and of the inserted construct. The researchers show that it is inserted at a location where there is very little interaction with the authentic genes. And the number of inserted base pairs (4205) is minute compared with the salmon genome that numbers 2.97 billion base pairs (nucleotides). In other words, the transgene and the wild salmon are 99.99986% identical (Bodnar, 2019). Moreover, the growth hormone gene of the chinook salmon is almost identical to that of the Atlantic salmon; this is shown by BLAST comparative research (Bodnar 2010). The mRNA of both can be found in gene banks, S50867.1 (1138 base pairs) and X14305.1 (1169 base pairs) respectively. BLAST comparison shows that 90% of the nucleotide sequence is identical. If we compare the amino acid sequences of the respective growth hormone proteins, they appear to be even 95% identical. In sum, the GM salmon differs only just slightly from its ancestor, the Atlantic salmon. This also means that the only really new pieces in the genome are those from the ocean pout (plus the minute pieces of PUC9 (25 bp) and pUC18 (20 bp); Figure 1b. The researchers have chosen the regulating regions of the ocean pout because these always activate the genes that they regulate, so that these will always come to expression; the salmon’s own promotor gene for the growth hormone only does so in certain circumstances, like daylight and temperature. Therefore, the AquAdvantage salmon grows to its full weight much quicker than the wild ancestor, but it does not outgrow it. It does mean that the required amount of feed is 25% less for the same amount of fish; in fish farms feed is one of the major cost factors (Van Eenennaam, 2019).

In view of,

(1) the minute differences on DNA level between the ‘all fish’ AquAdvantage salmon and the wild ancestor, that are dwarfed moreover by

(2) the relatively large differences in the genomes between various salmon varieties caused by natural mutations,

(3) the timely consultation of regulatory bodies in the US and Canada by AquaBounty Technologies,

(4) the wealth of scientific data that this company has supplied to these bodies, and

(5) the large number of preventions take by the company,

I am quite surprised that this GM salmon has not come to the market yet in major quantities. The reverse is true. In the US, there is much political hassle now after lengthy procedures. In Canada they take a rather firm line, fortunately. Both in 2018 and in 2019, trade in GM salmon amounted to five tons.

So far, one of the major outputs has been an avalanche of superficial stories in newspapers and magazines on the state of affairs and the ‘progress’. Anastasia Bodnar even published a thirty year Regulatory Timeline on this issue, 14 April 2019. She also is the author of a number of informative and well-documented articles that I gratefully used (see above). But the most informative sources of this Essay are the Science Response 2013/023 of the Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat and the ‘free condensed information’ of 19 November 2015 on the FDA approval of the AquAdvantage salmon. It made very instructive and interesting reading to me. A must-read. One thing is for sure: these bodies don’t decide lightly. The Canadian legislation is quite product oriented and pragmatic. Its US counterpart is ‘event based’, as they call it themselves, meaning that each step in the process is to be justified scientifically, in other words in a ‘hierarchical’ construction of scientific knowledge. In comparison: EU policy is based upon the precautionary principle that virtually blocks the entry of all GMOs into Europe.

In part 1b of this essay I will deal with the procedures of admission and implementation.

Interesting? Then also read:

Omega-3 fatty acids produced from corn by marine algae

Genetically modified food

Modern biotechnology: does it develop too fast?

It is great blog post. I am Always read your blog. Helpful and Informative blog. Thanks for sharing these information with us.