When talking of technology, many people nowadays have ICT in mind. But then they neglect the major steps forward taken by the life sciences: all chemical and biological knowledge of living organisms. We keep discovering new phenomena. Naturally! Of course. Nature will surprise us again and again.

This is a preview of the book Naturally! Of course. How nature never stops surprising us (in Dutch) by Alle Bruggink and Diederik van der Hoeven. The book will be released November 11, 2019.

We delve deeper and deeper into nature’s mechanisms

We delve deeper and deeper into nature’s mechanisms

The pace at which we accumulate knowledge of life’s processes is staggering. We can almost track these down to the size of molecules. And steer them. We advance swiftly in manipulation techniques. But then, we discover that nature is not a passive object. It can resist our manipulations. Whereas a slab of steel or a piece of concrete don’t have defensive mechanisms, nature does.

A fine example of this is resistance: the phenomenon that a poison has less effect, the longer we use it. It may sound strange, but our knowledge of the phenomenon is just 100 years old, it was first discovered in 1914. At a smaller scale we can witness resistance if we try to keep our lawn clear from dandelions by mowing it. The first year we still succeed: we cut the flowers’ stems before they can produce any fluffs. But soon you will discover that a new kind of dandelions will take hold of your lawn: with an ultrashort stem. No longer attainable for the knives of the mowing machine. Only to be removed by poison or by use of a thin scoop. But if we use poison, we will run into resistance as well, sooner or later: plants and vermin become resistant to the poison. And then what? Do we need to develop new poisons all the time?

The role of genetic modification

Resistance is a major but often neglected problem. We run into it in the battle against vermin. The substances developed by industry hold out for a few decades; then they become ineffective. DDT delivered very important services to the allied invasion on the coast of Normandy, it kept soldiers free from vermin. But as early as 1948, there were flies that walked on DDT powder as if they were sorcerer’s apprentices; it did not get hold on them anymore. Since that time, we have worked our way through four generations of insecticides. The present generation, the neonics, will become ineffective within twenty years’ time. Will we stay in this treadmill? With antibiotics, the same story. There too, we need to come up with new substances all the time. In the field of herbicides, resistance has popped up even on the most powerful agent ever developed, Roundup. On cotton plantations in the US they have a lot of trouble now with a Roundup resistant amaranth, a kind of vegetable, that grows very fast and then prevents sunlight to get through to the cotton plants.

Surprisingly, the mechanism with which nature resists these agents is genetic modification. The resistant amaranth has simply collected a lot of anti-Roundup DNA in its genes. Science has discovered that DNA change is an entirely natural phenomenon. DNA appears to change all the time, for instance because mistakes occur when DNA is copied upon cell division. Or, are these really mistakes? As a matter of fact this continuous DNA change is a mechanism through which nature adapts to the ever changing natural conditions. If they continuously create small variations in hereditary properties, species can survive in the strongest individuals – those who are best adapted to the new conditions.

Naturally! Of course. The role of the microbiome

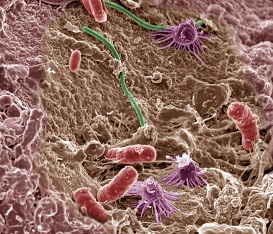

The part played by genetic modification is one of the ‘surprises’ offered to us by nature. Surprises unveiled by science at a high speed. Assisted by modern technology like the electron microscope. The microbiome too is such a surprise. We only recently learned about it through DNA analysis, twenty years ago we did not have an inkling of its existence. The microbiome in our guts, the ensemble of microorganisms that has a major influence on our health. To which it is hard to resist if it cries out: sugar! Or: salt! And even much richer and more diverse, the microbiome of the soil, that has much influence on the crop’s wellbeing. In the end we all depend on the proper functioning of this microbiome, because it is at the basis of our food supply. But then, fortunately, the microbiome itself does most of the work, in a way we can relax and just do ‘nothing’ except keeping it healthy.

Therefore, as modern science delivers us the tools to organize nature according to our needs, at the same time it teaches us modesty. Our proficiency lends us much more power; at the same time we learn that this power is limited. We learn that we cannot forge nature as if it were a slab of iron. We should no longer force her, but learn to understand her better and go along with her rhythm. Not subject her but waltz with her, so to speak. What such a waltz implies exactly, we will have to discover in the near future. Maybe we will even have to learn many more lessons in modesty. With that mentality we will enter a new era: a time in which we leave behind us reductionism and develop a new holism. An era in which we accept that all phenomena are interconnected. Naturally! Of course.

Interesting? Then also read:

Pesticide resistance, a growing problem

Can we engineer life? Golden rice

The shelf life of green chemistry