Modern biologists are waging a fierce debate on the meaning of the concept of the individual. Definitions of well-known phenomena like symbiosis and parasitism need to be rephrased. The debate goes beyond the world of plants and micro-organisms; the subject of the discussion includes mammals and therefore also mankind. We know for a long time already the importance of our intestinal flora, and accept the effects it might have on our behaviour. But admitting an effect on our way of life, our character and our genetic properties is surely a bridge too far – we think.

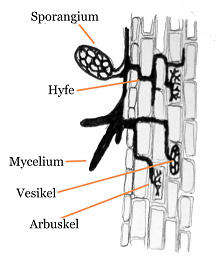

In nature, living together is the rule rather than the exception. We know for a long time already that plants need to live in symbiosis with fungi and bacteria in order to grow, to flower and to bear fruit. Modern biology allows us to study that community down to the level of the individual molecule. Through photosynthesis, the plant produces sugars and related products from CO2 and water for its own needs; and for all its cohabitants in and at its roots underground. In exchange, the underground community (fungi and several other micro-organisms) supplies the plant with nutrients like nitrates, phosphates and minerals. It is becoming increasingly clear that plants without such an underground community, a biome, do not exist at all. The debate now centres around the question whether this symbiosis is a collection of individuals (no matter how small) or a living entity. Some micro-organisms even live inside the roots of the plant. Fungal networks facilitate communication from plant to plant by transporting nutrients or by sounding alarm bells.

The ‘shortcomings’ of photosynthesis

Scientists consider photosynthesis as a complicated and rather inefficient process (that is a more an opinion than a scientific statement). Sometimes the process leads to products that are toxic to the plant itself. But if we should think that nature’s processes are inefficient or clumsy, this often shows just a lack of knowledge. These toxic compounds might very well serve an unknown function for some colleagues in the underground biome. Clearly: an individual plant or a single fungus or bacterium cannot survive. The entity we should take into account is a holistic one.

Let us consider lichens; the ultimate fusion of fungi and algae. Algae can perform photosynthesis and provide sugars and energy. Fungi take care of minerals, nitrates and phosphates. A cross-section of a lichen shows the separate parts of the algae and the fungi; in separation however they are not a living being. One might judge ‘So what’. But in the evolution, lichen have played an important role. They have facilitated the transition of algae from water to land and the development of land flora. And there is more. Lichen spores (their most simple form for survival) survive the most bizarre conditions; for instance the 24 hour temperature oscillation from -1200C to +1200C at the outside of the ISS space station; the interstellar space high vacuum, and a dose of cosmic or radioactive radiation 12.000 times the lethal dose for mankind. In short, the lichen spore is the ideal candidate for bringing life from anywhere in space to earth. As a pair!

Reproduction, always a challenge

We are all aware of the prime importance of reproduction in nature and the weird forms it may take. Look at the fungi that infect insects like house flies, cicadas or ants. The fungus grows inside their bodies, taking over several important functions and ultimately forcing the insect to climb or fly to high places where it gets stuck, and then release and spread the fungal spores for a next round. To complicate the concept of mutual dependency: many of the processes involved are propagated by micro-organisms such as viruses. So far, it is unclear what advantage the insects might have from this fungal cycle. But maybe that reasoning is somewhat too anthropocentric.

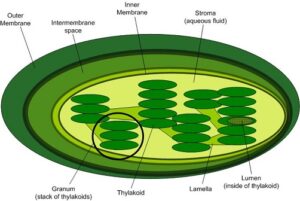

It is quite clear how these phenomena will heat the debate on the existence of an individual and the meaning of the term individuality. Even the well-known formula: Phenotype (appearance) = Genotype (hereditary makeup) + Environment is coming under pressure for renewal. We already know for a lang time how the mitochondria, the power stations of our cells, have migrated from ancient bacteria. The same holds for photosynthesis. The chloroplasts, the photosynthetic complex with chlorophyll as its most complicated molecule, descends from cyanobacteria. Probably, these were the first organisms able to make use of light for their survival. Also of interest to note is that chloroplasts and mitochondria have DNA of their own and their own means of reproduction. Albeit in conjunction with their partners.

Nature works efficiently and at times even gives the impression of laziness. Some functions have only been created/evolutionized once or in a limited number of appearances. Subsequently we find them operating in plants, insects and/or mammals. Nature shows us an increasing number of examples of properties borrowed from some other species followed by incorporation in the own genetic domain. With micro-organisms, exchange of genetic material is rather the rule than the exception. The news around the Covid-19 vaccine development shows us numerous examples. Mutations, genetic changes and the development of our immune system are by no means accidental events. They are regulated by mechanisms unknown to us until just recently; natural algorithms so to speak. Biology has now even developed a new specialism: epi-genetics, the subject that studies the interactions between Genotype and Environment. Unimaginable until quite recently. Not too long ago these entities were seen as mutually independent.

What about mankind?

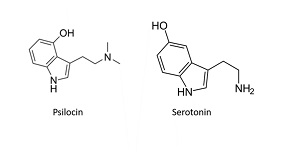

All well, you might say. This is all about little creatures and has no bearing on mankind. Alright, our intestinal flora is very important and is genetically much more diverse than ourselves. And yes, there are bacteria living in our mouths and noses that protect us from external threats. We admit that our skins are packed with yeasts and other small organisms of which we don’t know. But our intelligence and our consciousness make us quite different. Tricky concepts, in particular the last one. Intelligence is not unique to mankind nor a property of the individual. There is an increasing body of knowledge on the intelligence of animals and how this directs their way of life and their community. Moreover, what’s intelligence and what’s not? It exists in multiple forms. The intelligence of a flight of sparrows differs from the intelligence of an expert in nuclear technology. So does the applause after a magnificent performance of a Beethoven concert. An octopus has a lot of intelligence but no brains. A plant’s root system or a fungal network is immensely more clever than the sum of all their sensors in the root tips or the ends of the hyphal threads. Their communication system resembles a lot the functioning of our brains. Chemicals that play a pivotal role in the transport of (nerve) signals are very similar in mammals, plants and fungi. Serotonin in human beings, and psilocin in mushrooms are like brother and sister from a chemical point of view. The psychedelic effects of some mushrooms are effected by psilocin and allow us a small insight in (other forms of) consciousness.

The debate in biology is not yet coming to an end and some remarks in this column might go somewhat further than present scientific insights. Nevertheless, scientists agree that the importance of symbiosis in evolution has long been underestimated. There is growing support now for symbiosis as an important mechanism in the selection processes of evolution. Exchange of genetic information between symbiotic partners could very well have contributed a lot to this mechanism. It makes us understand how the mitochondria have made it to all our cells. And here is a lot more to debate in biology. It is becoming clear that evolution has been driven by much more than the mutual benefit of biological partners. It is a game with many partners and participants. The participation of several micro-organisms, viruses, bacteria, phages, yeasts and fungi alike, is increasingly coming to the forefront. While biologists were talking about a symbiont where two or three partners are living together, they now discuss holobionts and how many partners might constitute such a community.

In short:

– An individual species does not exist and a species means a community.

– An individual does not exist. Characteristics we consider as our individual property may be the result of the composition of our intestinal flora and the ‘decisions’ made there.

Our language often falls short in describing what happens in the world of plants and micro-organisms. We often use terminology laden with moralistic overtones or ambiguous meanings.

Want to read more?

– See the review by Javier Suárez in Symbiosis 76(2), pg. 77-96 (2018): The importance of symbiosis in philosophy of biology: an analysis of the current debate on biological individuality and its historical roots.

– Entangled Life, how fungi make our worlds, change our minds and shape our futures, Merlin Sheldrake, The Bodley Head, London, 2020. ISBN 9781847925190

– Bio-stimulants for sustainable crop production.Edited by Yoessef Rouphael, Patrick du Jardin, Patrick Brown, Stefania De Pascale and Giuseppe Colla. Burleigh Dodds series in agricultural science, 2020. ISBN 9781786763365.

Interesting? Then also read:

High hopes for holism

Can we engineer life? Plant gene technology, the photosynthesis boost

Pesticide resistance, a growing problem