In 1890, Robert Koch appoints Paul Ehrlich his assistant. Although Ehrlich (1854-1915) is above all a medical doctor (together with Emil Adolf von Behring he develops a vaccine against diphtheria), he is primarily fascinated by chemistry.

Project ‘100 years of antibiotics’

Episode 1. Louis Pasteur vs. Robert Koch

Episode 2. Paul Ehrlich, Salvarsan and chemotherapy

Episode 3. Mercurochrome, Ehrlich’s chemotherapy the American way

Episode 4. The rise of chemistry

Episode 5. A colourful foreplay

Ehrlich and chemotherapy

Once upon a time all disease control with chemicals was called ‘chemotherapy’ (a term we now reserve just for control of tumours). There was a theory underlying this term. It starts with the effect of dyes on a great number of tissues. Dye chemistry reaches great heights in Germany by the end of the 19th century. Dyes are mainly applied on textiles; but there are many other applications like tissue characterization (cells, muscles, nerves) and microorganism characterization.

Part of the dye molecule binds to the tissue; another part of the molecule causes the colour (the effect), by itself or together with the tissue. Ehrlich reasons that this ‘other’ part may be changed in such a way as to have an effect on a pathogen. This implies that we should be able to make logical chemical changes in the original molecule, with the goal of developing a medicine.

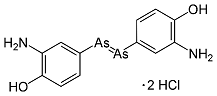

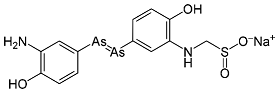

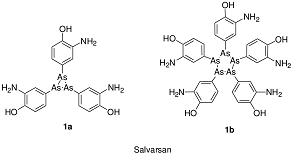

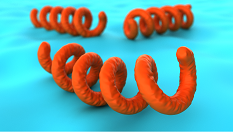

Healthy cells and body parts should not be affected. He terms this approach ‘rational design’ and hopes in so doing to find the miracle bullet that will kill the bacterium without harming the patient. After a long search, in 1909 he finds preparation 606 that kills the pathogen that causes syphilis. Although it is a Japanese, Sahachiro Hata, who finds this effect of Ehrlich’s compound in animal tests. At that time, discovery of the bacterial spirochete that causes the condition is just 4 years ago; following up Robert Koch’s famous work in this area.

To Ehrlich, Salvarsan confirms his theory. According to him, the toxic arsenic kills the spirochetes, a sub-family of the bacteria; whereas the substituted aromatic rings attach to the bacteria. The well-known Hoechst company produces the medicine; for them it is one of their first successes in medicinal chemistry. For over 20 years, Salvarsan and Neosalvarsan are the only medicines against syphilis. At first, they are administered orally (through the mouth). But Alexander Fleming (who later discovers penicillin) develops a better and less painful administration: intravenous (with a syringe), at that time a new method. Fleming is one of the few doctors in London who administeres Salvarsan; he treats such a number of patients that he is nicknamed ‘soldier 606’.

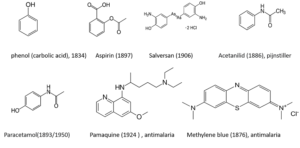

Synthetic chemistry

Salvarsan is one of the first examples of medicines produced through synthetic chemistry. One might argue that aspirin, also a fully synthetic medicine, deserves to come first (produced from 1897 onwards), but this compound was inspired by salicin from willow bark. The honour of being the first fully chemical medicine may be granted to methylene blue (1876). It is one of the many textile dyes, but later on it appears to be an excellent antimalarial agent. It turns out to be not very popular among patients, because it colours them intensely blue. But it does trigger a lot of research; among others on quinine derivatives. One of the important results is the well-known chloroquine (1932, now a much-debated agent against Covid-19). Another good candidate for being the first synthetic medicine is acetanilide. It is introduced on the market in 1866 as an anti-inflammatory agent. Soon, doctors discover that they can also use it as a pain killer, and therefore it is administered to people suffering from a headache, menstrual pain and the like. Only in 1948, researchers discover that acetanilide is toxic; the body processes it into paracetamol and toxic aniline. The first mention of paracetamol, by the way, dates from 1893. It is first synthesised in 1877. But it doesn’t grow into a popular pain killer until after ca. 1950.

In discussing these medicines, we look at the internal use. For external use, it is more difficult to establish when this practice started. Phenol (carbolic acid) may be the first chemical agent; it is introduced in 1834 as a disinfectant. The book ‘Creative Chemistry’, published in 1919, mentions the dyes malachite green, brilliant green, crystal purple, ethyl purple and Victoria blue, in use as disinfectants on soldiers in WW I, causing them to look like a ‘coloured Easter egg’.

N.B. In 1908, Ehrlich is awarded the Nobel Prize for medicine, together with Ilja Iljitsj Metsjnikov, for their contributions to understanding the reactions of our immune systems. Well before the Nazis remove all researchers of Jewish descent from the books and ban the Nobel Prize.

Sources:

Wikipedia: all names and products mentioned

The discovery of penicillin (New insights after more than 75 tears of clinical use). Robert Gaynes, Emerging Infectious Diseases 23(5), 849-853, 2017.

Indusrial Chemistry, Riegel, 4th edition, Reinhold Publ. Corp. New York, 1942

Wetenschap overwint de microben. G.Venzmer (Dutch translation K. Frits). Roskam publishers, Amsterdam, 1943. This quite accessible book has been published by a controversial publisher. Roskam published some 130 titles during the occupation of the Netherlands by Germany. These comprised some twelve military works, and about thirty books that fitted nicely in the national-socialist ideology.

Creative Chemistry, Edwin E. Slosson, Garden City Publ.Co., New York, 1919.