In 1937 already, the medical profession in the United Kingdom, France and the United States recognizes the major importance of the sulfanilamide and the other sulfas; for different reasons in each country.

Project ‘100 years of antibiotics’

Episode 8. The success of the sulfas; with a black rim

Episode 9. In the crossfire

Episode 10. International recognition

Episode 11. Pride comes before a fall

Episode 12. Lessons learned

International success of sulfanilamide

France didn’t know a tradition of patents on medicines; therefore Roussel can start producing Prontosil in 1935 already. That same year, Rhone Poulenc and the Pasteur Institute start a common research project, after Hörlein’s example. Within a few months, they score their first success: the discovery that the active ingredient is not Prontosil, but the simple metabolite (degradation product) sulfanilamide. ‘Colourless products have the future’, becomes the new slogan. But they take great care not to damage Hörlein’s and Domagk’s reputations. Behind the scenes however, the Pasteur Institute views Prontosil/sulfanilamide primarily as a threat to its proceeds from vaccines. The real breakthrough comes only at the 1937 World Fair, where Domagk is awarded a gold medal.

Medical doctors in the United Kingdom tend to be sceptical about chemotherapeutic antibiotics; moreover, there is a tendency to downplay new medicines arriving from industry. In October 1935, Hörlein lectures before the Royal Society of Medicine in London. This lecture turns out to be very successful: after some initial reservations, many research projects on Prontosil get underway, including animal and clinical tests. Initially still with limited success, and with much doubt on the German claims. Then, two publications in the Lancet in June 1936 break the tide, although enthusiasm never goes as high as in Germany. The Times too reports about the news. As the medicine is applied in increasing volumes, doctors started to moan about the ‘monstrously’ high price: up to 3 to 4 pounds per patient treated. Bayer lowers the prices, and in addition to that speeds up the introduction of the cheaper sulfanilamide. Maybe they intend to cut short competitors; anyway, if the buyer hasn’t expressly specified a preference for the red product, Bayer sends the colourless sulfanilamide on each demand for Prontosil. By the end of 1936, the English press already speaks of one of the most important medical discoveries of the century.

It is not until September 1936, when the news breaks to the United States. There is just a feeble response. Until in December, the president’s son, Franklin D. Roosevelt Jr recovers from a life-threatening infection after having been treated with Prontylin (= sulfanilamide). Supplied by Sterling Winthrop Chemical Company, the American daughter of Bayer/IG Farben. According to one review, in May 1937 there are 13 companies already that can supply the medicine. Sulfanilamide is not protected by a patent, so anyone can enter the field. Finally, Paul Ehrlich’s chemotherapy has been proven. In the opinion of many Americans, the era of the miracle drugs has begun.

A scandal

Miracle drugs and big money – we suppose that they thought along those lines at the Massengill Company in Tennessee. Back then, sulfanilamide can only be bought in the form of tablets. In liquid form, it would be easier to ingest, for children in particular. At Massengill they devise Elixir Sulphanilamide, made according to the recipe outlined below, and marketed without much ado on September 4, 1937:

| Sulfanilamide | 58 pounds | Elixer flavor | 1 gallon |

| Rasberry extract | 1 pint | Saccharin soluble | 1 pound |

| Amaranth solution | 1 pint | Caramel | 2 fluid ounces |

| Diethylene glycol | 60 gallons | Water | 80 gallons |

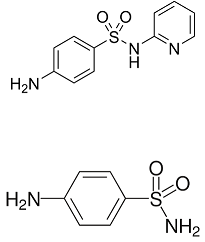

On October 11, six fatal casualties of the elixir are reported in Oklahoma. Soon, diethylene glycol is identified as the cause. On October 14, the FDA intervenes with much display of power. Of the 24 gallons produced, 11 gallons and 6 pints have actually been sold to patients; the death toll numbers 107 persons. Death only results after much agony and pain, lasting for 7 to 21 days. Massengill had done no research at all and had just assumed that glycols were a non-toxic class of substances with many well-known applications. Whereas the FDA has issued several warnings, a few years before, against the use of glycols in food. Because of these serious events, a long discussion on more powers to the FDA comes to a sudden end; it had dragged on for years. On June 25, 1938, the strict law comes into effect that is still the model for regulation. It coincides with the market introduction of the next successful sulfa drug: sulfapyridine, produced by the British company May & Baker.

Sulfapyridine, or M&B 693

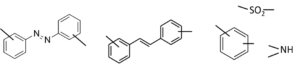

M&B 693 comes to the market with a bang, as the first medicine against pneumonia. It reduces the death toll from 1 in 5 to 1 in 25. It has taken a while for researchers to take sulfanilamide as the guide for research into new sulfas. Yes, the Pasteur Institute has proven that this substance is the active ingredient of Prontosil; but still for some time, researchers also take the other part of the substance, the azo benzene ring, as the starting point for further research. This also leads to a further study of stilbene.

The French company Rhone-Poulenc co-owns the British company May & Baker. They start a joint program for research on derivatives of sulfanilamide. The French will concentrate on variations in the amino group, and the English on the sulfonamide function. After having synthesized dozens of variations in the sulfonamide group, researchers at May & Baker find an old bottle containing aminopyridine. In the chemical logic prevailing at that time, not a very likely candidate for useful processing into a sulfa. But lo and behold: the resulting compound M&B 693 or sulfapyridine appears to be a very good medicine. Early 1938, a Norfolk farmer who suffers from incurable pneumonia is the first person to recover from this substance. The production of the first 100 kilos at May & Baker show much industrial bungling and improvisation. In particular the production of sodium amide, NaNH2 from sodium and ammonia at 4000C is a very risky devilry. But the product sulfapyridine is very successful. Within a couple of years, the new medicine outperforms Prontosil and sulfanilamide. The final breakthrough is Churchill’s rapid recovery from a dangerous pneumonia by the end of 1943, during a long trip to the theatre of war in the Middle East and North Africa. By the end of WW II, more than 5000 sulfas have been tested on their clinical usefulness.

Sources:

Wikipedia: all names and products mentioned

The First Miracle Drugs, How the sulfa drugs transformed medicine, John E. Lesch. Oxford University Press, 2007

No-nonsense guide to Antibiotics. Moira Dolan, SmartMedinfo, 2015