Both the UK and the US greet M&B 693 or sulfapyridine with much enthusiasm. In the war years, this message about the sulfas is a much-needed piece of good news.

Project ‘100 years of antibiotics’

Episode 9. In the crossfire

Episode 10. International recognition

Episode 11. Pride comes before a fall

Episode 12. Lessons learned

Episode 13. November 1921 and September 1928

Success of sulfapyridine

During the war years, the benefits of sulfapyridine are grossly exaggerated. Its side effects are hardly mentioned (the agent can cause kidney stones). But in the treatment of pneumonia and meningitis, sulfapyridine is very effective, it often makes the difference between life and death. It also deals effectively with measles and whooping cough. The end to all infections! headlines run. And it would win the war. There is some truth in this too. On the battlegrounds and in all English colonies, sulfapyridine is seen to be most successful. Churchill’s rapid recovery is another proof to this story. The press runs many different versions of the ‘discovery’ of M&B 693; all too often, they play a trick on reality. Some of them border on a personality cult. On the other hand: no one has ever received a Nobel Prize for this discovery. The enthusiasm does makes an early end to over-the-counter sales. Fortunately so, because many people started to use the medicine at random, and resistance laid in waiting.

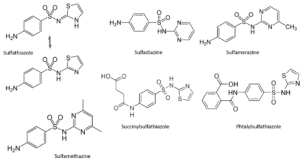

In the US, in 1937 already, more than a dozen companies are active in the field of sulfas, in the trail of the success of Prontosil/sulfanilamide. The most dominant ones are Merck and Sharp&Dohme, merged in 1953 to form MSD. Merck had grown big in the business of food supplements and vitamins, and develops a second business in the sulfas. M&B 693 is a great success in the US like in the UK, maybe even greater. The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and the American participation in the war are major stimuli to research and production. But Merck doesn’t succeed in developing a sulfa of their own. That is done by Sharp&Dohme in particular, and also by American Cyanamid. During the war years, some six second generation sulfas come to the market; most of them developed in the US. Germany and France are not very successful in this area during the war. Looking at the structural formulas, we witness to what extent Paul Ehrlich was right in his theory on chemotherapy and the structure/effect relationship. Colour has disappeared from the products. Maybe the heterocyclic substituent has assumed that role. And Ehrlich finally receives the well-deserved honour from the American and the English press.

The search for new sulfas

Through contemporary eyes, it would seem easy to find a new sulfa. As long as one leaves the sulfanilamide basic structure intact, there appears to be some clinical effect. In reality, researchers have produced and researched thousands of different structures in order to arrive at productive agents. Attaching a heterocyclic structure at the sulfanilamide side appears to have its benefits; probably the somewhat acid nature of these compounds enhances solubility in bodily fluids. The heterocyclic group reinforces the acidity of the sulfonamide proton. Substitutes on the left-hand side (on the para-amino function; succinyl and phtalylsulfathiazole) may result in better survival of the compound in the intestinal tract and promote the concentration in the blood; but then, these groups have to be removed in the body for the molecule to have its healing effect.

The sulfas mechanism

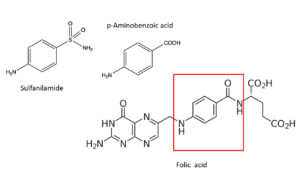

In 1940 already, researchers are convinced that sulfas operate through the blockade of an important enzyme in the bacterium; this will not kill it but prevent its development. Alexander Fleming is one of the researchers involved. By that time, it has also become clear that p-amino benzoic acid plays a key role. And researchers already infer that an enzyme is required for producing or processing p-amino benzoic acid. Now we know that the mechanism of the sulfas is based on blocking the formation of folic acid in the bacterium. This prevents the bacterium from synthesizing some proteins and nucleic acids, building blocks of its DNA; it therefore stops growing and reproducing. We now also know that sulfanilamide blocks the enzyme that inserts p-amino benzoic acid (in the red square) into folic acid. The three-dimensional structure of sulfanilamide resembles much that of p-amino benzoic acid. Sulfanilamide might just fit too well, sticking onto its place and preventing processing of p-amino benzoic acid. We now have also unravelled this enzyme’s structure (a protein consisting of some 300 amino acids); and the code and location for its production in the bacterial DNA. Mammals (and hence human beings as well) produce folic acid through a different pathway; therefore, sulfanilamide doesn’t block our bodily processes.

Research on sulfas in the first war years is exciting; and not just because of the magnificent results produced in patients and war casualties. Ehrlich’s chemotherapy is being perfected. Researchers are caught by the idea of establishing a relationship between chemical structure and clinical effect. With such a relationship, they would be able to design the chemical formula for the medicine appropriate for any condition – for cancer in particular. Rational design of medicines. But that clearly appears to be a bridge too far. A ‘rational’ therapy for cancer never materializes. And researchers do not succeed in discovering new sulfas. In fact, the theory developed later shows that the best sulfas had already been found. A sobering conclusion.

Rise and fall

In short, the heydays of the sulfas are in the first years of WW II. The bombast of the pre-war messages was even overtaken by reports on the ‘miracles’ done by sulfas in military wards. The sulfas were poured into the wounds for disinfection and administered as tablets in order to fight the bacteria from within as well. Because doctors have access to these medicines, survival rates of infections and injuries are much higher in WW II than in WW I. To which also contributes the use of blood plasma and blood transfusions, heart and lung surgery, a vaccine against tetanus and antityphoid and antimalarial medicines. But then penicillin arrives, that outperforms many of these developments. Achievements of the sulfas in particular.

In 1943, sulfa production in the US peaks at 8.7 million pounds, about 4000 tons. Until about 1960, the sulfas are in use as important anti-infective agents, In the Western world, just one sulfa has survived in the competition with other antibiotics: sulfamethoxazole, developed by Hoffmann la Roche and marketed from 1961 onwards. By far the most important application is in infections of the urinal tract, combined with trimethoprim and marketed under names like Bactrim, Septra or Co-Trimoxazole. This combination is also in use for the treatment of some kinds of pneumonia and as a part of a therapy against HIV/AIDS. It is interesting to note that trimethoprim too, blocks an enzyme essential for the synthesis of folic acid. And finally, we should mention the veterinary use of sulfas. The Merck company, mentioned already, partly owes it success in the veterinarian branch to the sulfa sulfachinoxalin, the first example of a medicine coming to the market mixed with animal feed (1948). Even in the area of agricultural chemistry, sulfas appear; the first example is the weed killer Asulam, produced by May&Baker, and marketed from 1965 onwards.

Still hanging on

In the chemical structure of sulfamethoxazole it is remarkable how closely it still resembles the original formula of sulfanilamide. The 2006 Merck Index, containing all medicines known back then, mentions about 40 sulfas; the most newly developed stem from the ‘70s, all of them based on Domagk’s sulfanilamide. In Asia, sulfas are still in use for the treatment of various infections. They are sometimes mockingly called ‘the poor man’s penicillin’.

Sources:

Wikipedia: all names and products mentioned

The First Miracle Drugs, How the sulfa drugs transformed medicine, John E. Lesch. Oxford University Press, 2007

No-nonsense guide to Antibiotics. Moira Dolan, SmartMedinfo, 2015

The American Synthetic Organic Chemicals Industry: War and Politics, 1910-1930. Kathryn Steen, The University of North Carolina Press 2014. ISBN-13: 978-1469612904 ISBN-10: 1469612909