The metaphor of a football game befits our theme. Football is war, isn’t it?

Project ‘100 years of antibiotics’

Episode 14. Riddles and coincidence

Episode 15. Historic antibiotic agents

Episode 16. The Sulfas have the upper hand

Episode 17. The Oxford team

Episode 18. Penicillin beats the sulfas

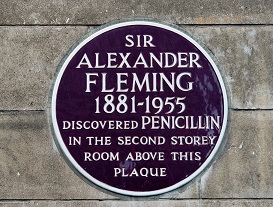

Let’s take the years 1920-1950 to be a 90 minute match. The competing teams are the German Sulfas and the British Pennis. They compete for the very desirable Bacillus Beaker trophy. In previous training matches, the Germans seemed to be superior, with strong defenders like Koch and Ehrlich. Their coach Hörlein has a firm hand and their forward Domagk has a formidable shot. There are hardly any well-known players in the British team. Some may know the small Scotsman Alexander Fleming with his deep blue eyes. In his youth, he played in the Scottish team the ‘Salversans’ and was nicknamed Soldier 606. The match starts in 1920, the first one between Great Britain and Germany after WW I.

A match

The Germans kick off and the first half hour develops as expected: the Germans have the upper hand. But they don’t score. The only real counter by Great Britain is in 1921 with a nice cross by Fleming, but without any result. Then luck seems to be on the side of the British. In 1928, the small Scotsman counters and kicks an unstoppable shot right in the middle of the post of the German goal. The match heats up in the last quarter of the first half. The always dangerous Domagk kicks the ball at full speed on the goal post. Soon thereafter he is more successful. In the last minute of the first half Domagk scores a magnificent goal, in 1935. Its nickname is ‘Pronto’, with the promise that soon more will follow. German coach Hörlein receives a warning from the French referee of the Pasteur team, not to meddle with the game anymore.

Half-time. In the British changing room, the team discusses feverishly. They decide to change three players, the maximum allowed, taking the major risk that they would have to continue with ten (or even less) players after an injury. The players of the well-known English May&Baker team are all substituted by three Oxford players: Howard Florey, Ernst Chain and Norman Heatley. Fleming moves to the left defender position. It is a wild gamble, with resounding success. In 1939, 1941 and 1944 the British team scores, three times in total. Domagk receives a red card and Hörlein, the German coach, is even being removed from the stadium. After 1944 there are many dangerous moments, but neither team scores anymore. The British team wins 3-1.

Practical problems

Back to 1928. Why would it take more than 10 years for penicillin to make a breakthrough? Fleming tests his broth on the mucus of the sinusitis of his colleague Craddock. Three hours later, 99% of the bacteria have disappeared. This seems to be promising, but Fleming isn’t satisfied. How on earth could one present such an impure broth as a medicine? He fears a major allergic reaction (anaphylactic shock) if patients would be administered this fluid. He investigates the effect of administering a filtrate of the broth on a severely infected leg but finds hardly any effect. Fleming judges that his agent is too weak and too impure. And the effect disappears after some tine. Thinking that his agent is an again enzyme like lysozyme, he names the filtrate penicillin.

Subsequently he searches a chemist. Again, he cooperates with Ridley who also helped him in lysozyme purification. But they and Craddock fail to produce a convincing result. Careful concentration produces a brown sludge, that does have a much increased antibacterial effect. After some months, they give up. On February 13, 1929, Fleming presents his findings in a lecture to the Medical Research Club. With just as little response as on his stories on lysozyme. He plods on until 1935 and in those years writes two papers on his work. Again, without much response; and again because they are quite short and do not show much practical detail.

The sulfas are in the lead

Other chemists in England have a bit more success. For instance, they find that the mould grows well on a substrate of glucose and water, with minerals like sodium, potassium, manganese and iron. Much more easily than on a half-digested bull’s heart. Moreover, penicillin appears to be rather insensitive to acids; and it can be extracted by alcohol from the mould mixture. The even succeed in extracting penicillin from water with acidified ether. But after that, they cannot purify it anymore. There is still some progress on the clinical front: infections of the eye can be treated externally with it. Then in 1935, the discovery of the sulfas gives the final blow to any interest in work on penicillin. Although Fleming does keep on breeding his penicillin mould, if only because with it, he can cleanse his petri dishes from unwanted bacteria.

With today’s knowledge, we understand quite well the unfavourable results of Fleming and his colleagues. Penicillin is not an enzyme, but a rather small molecule with a rather low stability. Temperatures should stay below 20oC at all times. The substance is notoriously difficult to crystallize. Moreover its structural formula, viewed from the chemical knowledge of the time, is not obvious at all. Fleming was a clumsy man with a miserable PR. But his discovery is of major importance. Many historians have a problem giving an adequate description of both the man and his work.

Sources:

Wikipedia: all names and products mentioned

The Mould in Dr Florey’s Coat. Eric Lax, Abacus 2004. ISBN 978-0349-11768-3

Discovering: Inventing and Solving Problems at the Frontiers of Scientific Knowledge, 1st Edition by Robert Scott Root-Bernstein ISBN-13: 978-0735100077 ISBN-10: 0735100071 Replica books 1997