There are four developments that mark the year 1950 as a turning point in medical history: (1) the overwhelming success of the penicillins, and additionally the cephalosporins and streptomycins, (2) the discovery that life becomes bearable to rheumatic patients through the cortisone hormone, (3) the irrevocable proof of the causation of lung cancer by smoking by (4) statistical research on large populations. Some start speaking of a golden age of effective medicines. Even if we should look upon the major achievements of sulfas and penicillins as events come about by chance, now people start to believe in the engineerability of new medicines and medical practices. The end of the world wars and the economy of recovery add to the new vision.

Project ‘100 years of antibiotics’

Episode 30. Cephalosporins

Episode 31. Help from an unexpected source

Episode 32. Turning point for the good

Episode 33. The engineerability of life

Episode 34. The golden age 1960-1980

From the doctor to statistics

From the doctor to statistics

In the last episode, we discussed how chance and luck join miraculously in the discovery of new medicines with the use of statistics and research on major populations. Firstly, there is the discovery that the combination of streptomycin and 4-amino salicylic acid appears to be very effective in containing tuberculosis; this is just the beginning. More important is the proof beyond all doubt that smoking is a cause of lung cancer. From 1950 onwards, randomised research with a control group is common practice in the development of new medicines.

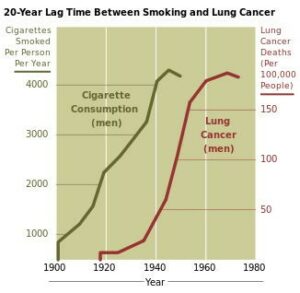

But use of statistics and mathematical models does run into resistance. Many doctors look upon this as an assault on their authority. Moreover, back then knowledge of and insight into the proper use of statistics is not widespread; certainly in the realm of healthcare. And yet, at this moment the foundation is being lain. The convincing proof of the causal relationship between smoking and lung cancer primarily stems from a major investigation among 60,000 medical doctors on their smoking habits and death figures over a period of two and a half years. Considering all fatalities in the period of investigation, the relation between smoking frequency and number of cancer deaths is the only relationship that holds.

Statistical relation-ships between lung cancer and smoking

Forty years later, in 1993, researchers have taken another look at this study. About half of the original participants has then passed away already, of which 883 from lung cancer. Conclusion after some maths: men smoking a pack of cigarettes or more daily, stand a chance 25 times as large of passing away from lung cancer than non-smoking males. Those who attributed the cause to motorised traffic, or to the large number of roads covered in tarmac, lost the debate for quite some time then.

Sometimes, statistics show wonderful relationships, but in other instances these relationships have little or nothing to do with cause and effect. Like the fact that around 1950, the incidence of deaths by tbc in the Western world is almost as high as that of deaths by lung cancer. Albeit falling in the first case, and on the rise in the latter. Or take that Finnish study on a statistically proven relationship between cancer and use of antibiotics. Yes, it is a fact that cancer patients more frequently use antibiotics. But cause and effect are not clearly linked in the publication. And yet, the researchers entitle their article: Antibiotic use predicts an increased risk of cancer.

Euphoria

These events lead to a sense of euphoria; together with the discovery that the cortisone hormone from our adrenal glands can suppress for quite some time the symptoms of the nasty common disease rheumatism (more precisely rheumatoid arthritis). The motion pictures of rheumatic patients, one upon a time confined to their sickbeds, and later walking or even dancing, are shown all over the world; this turning point boosts the image of the medical profession. The element of chance in the discovery and development of almost all antibiotics are forgotten. The creed now is: we control the conditions. The proof of the risk of lung cancer caused by smoking adds to the optimism. Surprisingly so, judging by today’s standards. But back then, people were convinced that bad habits can be turned around through education and sensible politics.

In sum, the euphoria was based on two factors:

– the proof that diseases can be cured, given the proper medication;

– the conviction that bad habits can be turned around.

In other words, we can engineer life. Some problems might not be cured right away, but you can count on us. Solutions are underway.

Successes keep coming

As a matter of fact, successes keep coming. The fifties witness major progress in psychiatry. After this turning point, depressions and schizophrenia can be handled more effectively. Medicines like chlorpromazine and azathioprine are still on the market; together with a large number of other sedatives. From 1955 onwards, open heart surgery makes much progress. At first with volunteers by the side of the surgery table, lending their heartbeat to sustain the patient’s blood circulation, later with the heart-lung machine and heart transplants. From 1963 onwards, kidney transplants are in the medical practice. The development of the pill also contributes to the frame of successes and the concept of the engineerability of life. Like IVF babies.

Sources:

Wikipedia: all names and products mentioned

“The Rise and Fall of Modern Medicine”, James le Fanu, Carroll & Graf Publishers, New York, 2002, ISBN: 0-7876-0967-7

Antibiotic use predicts an increased risk of cancer, Annamari Kilkkinen, Harri Rissanen, Timo Klaukka, Eero Pukkala, Markku Heliövaara, Pentti Huovinen, Satu Männistö, Arpo Aromaa, Paul Knekt, 25 August 2008 https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.23622