PFAS is a generic term for a large group of fluor containing organic chemicals. They are being used as water repellents, like in non-stick pans, paper and coatings, packing materials for food, dust repellent sprays and coatings, fire extinguishers, surface active compounds, paint, inks, adhesives, biocides and more. There are thousands of PFAS. These have one problem in common: they hardly break down in the environment. For that reason they are also termed ‘forever chemicals’.

PFAS are everywhere

We now find PFAS anywhere in the world, including in polar areas. Most are perfluorated compounds, carbonic acids, sulfonic acids and fluor polymers. Generally, they are water solvable and very mobile in the environment. And very badly downgradable, something that contributes to their popularity as protective compounds. But precisely because of that, they concentrate in the environment – while they are toxic to living creatures. The European Food Authority EFSA tries to issue a ban on PFAS as a whole.

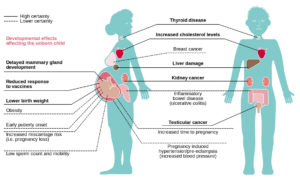

New knowledge shows that these substances are toxic to humans, already at concentrations of nanograms per litre. In the new Dutch drinking water regulations therefore, PFAS are part and parcel of the set of substances to be monitored. Apart from that, regulation is on its way. Drinking water companies and district water boards favour a national and European ban on PFAS.

Breakdown, a difficult problem

In recent years, research has started to investigate PFAS breakdown. The latest news in this series comes from water technology institute Wetsus in Leeuwarden (the Netherlands). According to researchers Jan Post and Amanda Larasati, they found a groundbreaking solution. First of all, they concentrate the substance in water – which will render treatment more efficient and therefore cheaper. They absorb the substance to a ring-shaped molecule – patented by now. They can reuse the ring some tenfold by rinsing it with alcohol. To that, they add another (as yet secret) compound that breaks down PFAS. Published in the German journal Angewandte Chemie.

But this is just in the research phase. Can it be scaled up to an industrial level? Wetsus contacted three universities in search for an answer. And they are in contact with a production company. Even so, the main problem will be marketing the equipment. In order to sell it, they need to arrive at a competitive price. But unfortunately, they cannot yet estimate the costs incurred. Market introduction may still take some ten years.

Slow progress

Other institutes now also research PFAS breakdown. Incineration doesn’t seem a good idea, for breakdown only seems to take place at very high temperatures, above 1600 oC. Bacterial breakdown does seem doable, but slow. Removal using adsorbents and ion exchange equipment will just stir up another problem – for what to do with substances that have absorbed PFAS?

How to proceed? Recently, Science magazine ran an article on the successful breakdown of PFAS. The authors used dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) as a solvent, adding just sodium hydroxide. They heated the mixture to between 80 and 120 oC. But this will break down just the longer chains, whereas the shorter ones (often the most problematic ones) remain largely intact. Moreover, results were obtained in rather concentrated solutions, whereas in actual practice the problem comes from very diluted solutions. Here as well, practical applications seem to be a matter of the long term.

Ultraviolet light

Another pathway for breaking down PFAS was developed by researchers of Riverside University in California. First, they pumped hydrogen into the PFAS containing solution in water – this rendered more active the molecules – and then irradiated the solution with strong ultraviolet light. According to them, the PFAS disintegrate to small harmless particles not containing any side products or impurities.

Researchers at Clarkson University in New York developed a more exotic variation. They mixed PFAS and additives with metal bullets. Then, they made them crash at high speed; this broke down the carbon-fluor bonds. They added boron nitride, a piezo electric material that can absorb electrons when deformed by mechanical forces. Then, this activated compound will react with PFAS.

Filtration

Researchers at the University of British Columbia tried to achieve the same, from another angle. They filtered the contaminated material through silicium dioxide. And then, they broke down the absorbed compounds by light and electricity. According to the researchers, they can reuse the filter material several times.

But according to Jacob de Boer, professor emeritus in environmental chemistry and toxicology, there will not be one single solution to all problems. De Boer has a track record of 48 years, investigating persistent substances. He doesn’t think there is a holy grail to get rid of PFAS. ‘I expect several technologies to exist alongside each other,’ he says. Like many others, he is a proponent of a ban on PFAS. ‘Chemistry is very creative indeed,’ he says. ‘There is bound to be an alternative out there.’

Ban

The Netherlands, Scandinavian countries and Germany have submitted a proposal to the European Commission for a ban on PFAS. Industry can come with a counterproposal within a year. But even if a ban would be filed, it will take effect in two years at the earliest, De Boer estimates. Industry could even keep on producing until 2040, until an alternative should have been found.

Nevertheless, we have a major problem. ‘This kind of substances is not only a problem to us, but also to generations to come,’ De Boer tells change.inc. ‘It is pure madness. Techniques to get rid of PFAS need to be developed, but in order to arrive at a cleaner and more liveable world, we need much stricter policies as well.’

Interesting? Then also read:

The role of chemistry in the reduction of plastic waste

Chemical recycling of mixed plastic waste

Chemicals and materials industry needs to innovate

The article provides a hopeful outlook on resolving the PFAS issue, highlighting innovative solutions and regulatory efforts. It’s encouraging to see progress in tackling these persistent chemicals and moving towards a safer, sustainable future. Great read for anyone concerned about environmental health!