Do we need carbon capture in order to meet climate goals? The jury is still undecided. If we would like to keep on using fossil fuels, we need carbon capture in order to keep CO2 levels down. But application of the technology makes little progress. Wouldn’t it be easier and faster to concentrate on renewable sources? Natasha Gilbert wrote a clarifying article on the subject.

In spite of much publicity on the subject, actual results are still far from what we would need. Global CO2 emissions are at an all-time high. Last year, they amounted to 35.8 billion tons. Contrast that to one of the most successful carbon capture projects – that of the Sleipner gas field, 200 kms off the coast of Norway. There, we strip carbon dioxide from natural gas — largely made up of methane — to make it marketable. The CO2 is not released into the atmosphere, it is buried. In the project, we store around 1 million metric tons of CO2 per year. It is praised by many as ‘a pioneering success in global attempts to cut greenhouse gas emissions’. But it amounts to less than one thousandth of the effort we need.

Six years to go

Gilbert doesn’t hesitate to note that we just have roughly six years before we exceed the 1.5oC level over average preindustrial temperatures; the internationally agreed-upon limit. (Even though we already exceeded this threshold over the past 12 months). Many hold that just renewable energy will not be sufficient to meet global CO2 targets. That would imply a much more rapid change than we witnessed in the recent past. If so, we need CO2 capture and storage. In order to half emissions by 2030 and to reach net zero emissions in 2050.

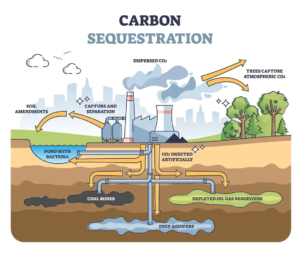

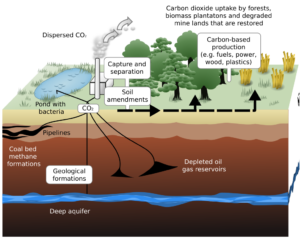

Carbon capture and storage, often abbreviated to CCS, is a major receiver of government funding. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), public funding for CCS projects amounted to $20 billion in 2023. Often, CCS is used on CO2 resulting from coal or natural gas power generation. It is then compressed into a liquid and stored in porous rock formations; or reused, for instance to produce cement or to enhance oil production. This is a technology much promoted by governments and industry. But with very little result in terms of diminishing CO2 release into the atmosphere.

Do we need CCS?

Some people argue that the situation is urgent; therefore, so they hold, we need CCS. Others see this as a means to continue the use of fossil fuels. They say it’s better not to emit in the first place. Whereas CCS will essentially perpetuate fossil fuel use. But people don’t know what could come next, and therefore psychologically hold tight to fossil fuels.

These considerations move the attention away from the question that really matters: will CCS projects ever lock away enough CO2 to really contribute to climate mitigation? Or are they just a pretext for a lack of action right now? Just 12 of the 41 existing projects inject CO2 with the exclusive aim of storing it underground. And of those 12 projects, half are involved in enhanced methane production – which upon burning will produce CO2 once again.

Cement industry

Much CO2 is being emitted in cement, and in iron and steel manufacturing: each produces 6 to 9 percent of global CO2 emissions. Only one project, a steel factory in Abu Dhabi, captures CO2. There are no projects that capture CO2 from cement manufacturing. There is just one project that captures CO2 directly from the air – in Hellisheiði, Iceland. And there are smaller projects; for instance sealing the gas in concrete.

Already a decade ago, Sally Benson and Heleen de Coninck wrote about the slow progress of carbon dioxide storage projects. The result of a lack of public policies that support these technologies. For instance, there are no government subsidies to make it cheaper to bury emissions underground than to emit them.

Capacity falls short

But this may change. The Global CCS Institute notes that in July 2023, 351 new commercial-scale projects were underway. Many of these projects will bury CO2 underground. But some will still release the CO2 again, for instance because they will enhance methane production. And if we add up these efforts, they are still a far cry from what we would need. If all projects would come online, according to Sean O’Leary of Ohio River Valley Institute, they would capture a few hundred million tons, about 1 percent of global carbon emissions.

Moreover, in this field projects rarely meet their stated goals. An analysis by the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis of 13 key CCS projects, published in 2022, found that most failed to reach their targets. Some by an appreciable margin. This isn’t good news, as stated goals for CO2 capture fall far short already of the amount deemed necessary by the International Energy Agency (400 million tons in 2030, as compared to 1 billion tons). And some underground storage projects are halted because underground capacity appears to be limited, or because of uncertainty that CO2 will in the end escape into the atmosphere. As one experts puts it: ‘subsurface storage is by nature uncertain.’

Do we need to rely on CCS?

This raises the question if it would be wise to rely on CCS for climate mitigation. Shouldn’t we instead go for renewable energy? Complemented by planting and maintaining forests? At least for the majority of our efforts? Even though oil industry claims that recent projects perform better. But even the critical Rocky Mountain Institute judges that we need CCS. They do judge that ‘reduction should be prioritized wherever possible’. Nevertheless, we need CCS in order to reach the goals set. Action is needed now, they find.

But still, money is a problem. Costs may be very large indeed, if we should wish to capture an appreciable amount of the CO2 produced. Unmistakably, these costs will be compared with the costs of installing solar and wind power. These costs have one very important characteristic: they fall quickly. IEA estimates that between 2014 and 2027, costs of carbon capture will fall by about 55%. Compare that to historic price developments of solar energy: between 2010 and 2018, costs took a dive by 80%. A development that may not be as fast now, but which is still going on. In 2020, solar and wind power became cheaper than fossil based electricity in most countries. So how do you think the costs of these sources compare to fossil fuels or fossil-based electricity plus carbon capture?

Conclusion

Natasha Gilbert is reluctant to draw conclusions. But in the end, she notes that we have to reduce emissions fast now; rather than rely on CO2 removal in the long run. And the instrument to bring this about is clear. We shouldn’t forget carbon capture; but out main effort should be in promoting renewable energies.

Interesting? Then also read:

CCU, Carbon Capture and Utilization, even better than biomass as a feedstock

The many uses of carbon dioxide

Direct air capture of CO2: dangerous nonsense