Ocean habitats play a key role in storing carbon from the atmosphere; but until now, nobody has known exactly how much ‘blue carbon’ ends up in kelp, seagrass meadows, salt marshes and sediment in the seabed. Now, we tend to damage this carbon storage: by activities such as commercial trawling and destroying coastal wetlands.

A new area of interest

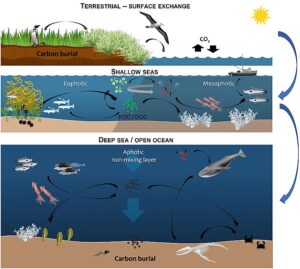

The carbon is being stored in wet locations easily overlooked. Scientists at the Scottish Association for Marine Science reveal that 244 million tonnes of organic carbon are stored in just the top 10cm of seabed habitats around the UK. Most (98%) of that is in mud or silt – a location that’s quite easily overlooked when it comes to conservation measures. Scientists have appropriately called this carbon ‘blue carbon’, carbon that is captured and stored by ocean habitats. When unharmed, marine habitats naturally absorb carbon and prevent it from being released to the atmosphere. But this has been difficult to establish.

The amount of blue carbon stored is staggering. In the United Kingdom, seabed habitats could capture almost three times as much carbon as UK forests do per year. This has huge implications. For if we know where the biggest blue carbon stores are, this should influence decisions about which areas should be prioritised as marine protected areas; whereas other areas may be better suited for future developments such as offshore wind.

A major carbon storage

As leaves fall aground in the forest, they store carbon as they disintegrate. Just like this, seagrass or kelp that break off get incorporated into the sediment and store carbon. The so-called plankton snow (dying plankton) is another major sink, it also ends up being stored as blue carbon. And just like plankton, the krill of the arctic seas stores much carbon (estimated to be at least 20 million tonnes annually) as their poo sinks to the deep ocean. Clearly, The Conversation writes, blue carbon is a significant global carbon sink. But if we continue to cut down, degrade and dredge these critical habitats, we will release all the stored carbon that has accumulated over thousands of years.

There is an important difference between carbon storage on land and in the sea. On land, all forests play their part. But coastal wetlands store up to 50% of the carbon held in the ocean, while occupying only 2% of the sea floor. Fairly quickly, carbon stored in the sea sinks to the bottom and stays there for at least 100 years. If we protect these carbon sinks, we may do a lot of good for the climate. But as we do not consider blue carbon in our national greenhouse audits, there are no strategies to mitigate such emissions.

Miracles

As research goes, marine scientists are now discovering the miracles of life in the seabed. Marine ecologists from the Convex Seascape Survey describe this ecosystem as a ‘bustling metropolis’ where burrowing lugworms, sea potatoes and bobbit worms mix sediments. We still have no idea of the amount of carbon being stored here, but scientists are making headway in estimating the amount of carbon being moved downward into the seabed. ‘It could be colossal’.

In South Africa, Jacqueline L. Raw, a marine researcher at the Nelson Mandela University, makes the first national blue carbon sink assessment. She focuses on mangroves, salt marshes and seagrass, although not mud and silt. But if left undisturbed and subject to certain conditions, these carbon stocks can build up over centuries.

Blue carbon storage

Blue carbon only emerged as a mainstream global climate solution relatively recently. Substantial discussions about blue carbon gained momentum in the run-up to the COP27 climate summit in Egypt in 2023. It would seem a matter of course, but until quite recently, marine sediments – and their climate protection potential – were overlooked as a carbon storage. Temperate areas have the highest potential for carbon storage. Like New Zealand, that hosts some ‘hotspots of carbon burial’. Scotland’s sea lochs need robust protection for this same reason. Blue carbon potential is now part of the selection criteria for sites designated as Highly Protected Marine Areas.

Indonesia may soon take similar steps. It hosts 22% of the world’s mangroves and 5% of seagrass meadows. Protection from industrial fishing, mass tourism and mining is set to increase. But critically, protecting seagrass is ‘quite tricky’ because an Indonesian seagrass map has not yet been completed. Only with baseline data and ongoing mapping can the amount (and potential decline) of blue carbon be properly monitored. The bottom of the ocean needs to become a top priority, and quickly so.

Interesting? Then also read:

The many uses of carbon dioxide

Towards net zero carbon emissions

Gunter Pauli and the ‘Blue Economy’