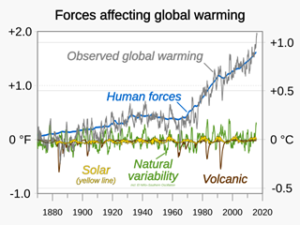

Increasingly, methane (CH4) emissions are on the critical path – the path towards limiting climate change to 2°C. This is the upper target of the 2015 Paris agreement. Methane emissions are rising very fast, says Euan Nisbet, a professor of earth sciences at Royal Holloway University in Great Britain.

Methane

Methane

At present, methane is the biggest culprit of global warming. Emitted in much smaller quantities than CO2, but it is a much stronger climate gas. It is responsible for more heat – but over a much shorter time scale, as methane is broken down quicker in the atmosphere. It lasts much shorter in the atmosphere (decades versus centuries). Reducing emissions of methane to the atmosphere could drastically slow the rate at which Earth’s climate is warming.

Each year, about 600 million tonnes of methane are emitted to the air, very roughly 40% from natural sources and 60% from human activities. Of this latter portion, fossil fuels contribute 120-130 million tonnes. This is methane that leaks from gas pipelines, coal mines and oil wells. There has at least been some progress towards controlling these leaks: new satellite technology has excelled at finding them, while 159 countries have pledged to cut emissions by 30% by 2030.

Agriculture

But the biggest human source of methane is agriculture. Nisbet has calculated that roughly 210 million to 250 million tonnes of methane come from agriculture and its products. Most of this is in the breath of livestock animals and their manure, and food rotting in landfills. Cutting agricultural methane emissions will involve a wide range of relatively cheap measures. They need good design and management, but could cut food-related emissions substantially over the next decade.

There are several options. Adding a layer of soil to a landfill provides habitat for methane-munching bacteria. Covering manure storage tanks, banning the burning of crop waste and only flooding rice paddies when necessary could reduce other methane sources. Such changes aren’t expensive or difficult.

Labels

But also, cutting methane emissions would mean having smaller herds. Meat production is a large source of methane gas. But we could easily have the majority of our protein intake from beans instead of meat. In doing so, our health would benefit along with the climate. Rearing meat is heavily subsidised, however. Every fifth dollar of public farming subsidy goes towards rearing meat. Much farmland is reserved for growing crops to feed livestock. Reducing this would also mean cutting the environmental, economic and social costs. We would have more woodland and grow more crops grown for human consumption.

Labels could indicate to consumers what the climate effect of their food choices would mean. As suggested by Yi Li, a senior lecturer in marketing at Macquarie University. In Australia, where Li is based, meat accounts for half of all greenhouse gas emissions from products consumed at home. Producing 1kg of beef may emit 60kg of greenhouse gas, while the same quantity of peas yields just 1kg of emissions. But while better informed consumers are important, the food system needs deeper reform.

Gas-tight covers

Cows, pigs and chickens make vast amounts of manure. In the US, Europe and East Asia, manure is often kept in big tanks or lagoons. These are usually under covers, but still release a lot of methane. Gas-tight coverings can prevent this, and the captured methane can be harvested and then burned to generate electricity. This still produces CO2, but the warming impact is smaller, while the electricity can replace new natural gas in the national grid. The remaining slurry can be turned into fertiliser. Though this is not commercially feasible now, it may one day be possible to turn it into aviation fuel.

Biodigesters are becoming common in towns and on farms, but are often very leaky. Methane doesn’t smell, but if a biodigester is releases other gases that stink, it’s probably also releasing methane. Leaks are easily controlled; but much tighter regulation is needed to ensure this happens.

Cattle

Most of the world’s cattle are in India, Africa and South America. In large parts of the tropics, rain-fed crops aren’t enough to sustain people. The difference is made up by meat and milk from cows and goats that browse trees and bushes and graze seasonal grasses.

Smaller herds can produce the same amount of food if cattle diseases are reduced. Bovine mastitis, East Coast fever and African trypanosomiasis can be vaccinated against, for example; and agricultural experts in India have even used artificial insemination to make more calves female, and so slash dairy cattle numbers.

Beans

Research has shown that flour made from broad beans is higher in key nutrients – protein, iron and fibre – than wheat flour. Bread, pasta, pizza, cakes and biscuits could increasingly be produced using broad bean flour, underpinning a shift towards more nutritious diets. Such a protein transition would also free up land for fruit and vegetable production for domestic consumption. In this scenario, we would be projected to eat 45% less meat and dairy; replacing them with alternative proteins – plants and synthetic foods such as those made from precision fermentation – a technology producing proteins that can be used in new alternatives to meat and dairy.

Labelling food could be an important way to inform people. With additional information about emissions, people might make better choices for the climate. Emphasising non-meat options and altering the layout of supermarkets may also help change the ‘choice environment’ and so change consumption practices.

Interesting? Then also read:

Towards methane mitigation

A plant-based diet would have a major impact on climate change

How to cover future protein demand?