We are now three decades into political and research efforts to stop climate change. But we are still in the era of rapid global emissions growth. Since 1990, we emitted more CO2 into the atmosphere than ever before. What is the cause behind this lack of success? It is power; manifesting itself in a dogmatic political-economic hegemony; in influential vested interests that narrow techno-economic mind-sets; and in ideologies of control. Says an article that appeared a year ago in the Annual Review of Environment and Resources.

If we should stay within the 1.5oC temperature rise limit, we should now reduce CO2 emissions at an unprecedented scale – given our inability to reduce these emissions in the past. Rates of mitigation will have to be above 10% per annum. Evidently, the world is not on this trajectory. As a consequence, ice caps continue to melt, weather extremes become business-as-usual and species come to the brink of extinction. In order to prevent such consequences, we need to understand why the world has shown so little response to overwhelming scientific evidence on climate change.

The Davos cluster

The authors identify three clusters of causes. The first they call the Davos cluster, by way of caricature. This cluster defines a paradigm of global debates that in practice excludes questions of corporate and official governance, vested interests of the fossil fuel industry, and geopolitics and militarism.

First of all, developed nations have failed to address climate change. They just haven’t shown leadership in this matter crucial to the future of our planet. Moreover, oil companies and their sympathisers have successfully developed hedging strategies. First, they tried to discredit the science of climate change. Now they have reverted to more subtle strategies, like promoting natural gas as a transition fuel. And finally in this cluster, changes are bound to be permanent. Any change in global energy production will mean a profound redistribution of global power. We will need to change sociocultural and political norms as well. Society would need to change! And this in itself is a powerful impediment to energy change.

The Enabler cluster

The second cluster, which the authors call the Enabler cluster, reduces all questions to those that fit within the contemporary socioeconomic paradigm. This cluster asserts the dominance of mainstream economics and finance, the techno-economic rationality of global mitigation models, and the technological determinism of large-scale energy supply. But precisely because this cluster relies so much on an apparently self-evident existing rationality, it could in principle also become a facilitator of rapid change.

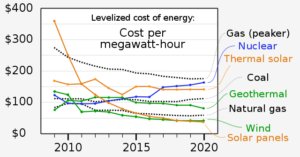

One of these self-evident rationalities is that of ongoing economic growth. Including, among others, the ‘financialization of the environment’. But how rational is this belief in ‘enabling’, given that it has been unable to deliver any tangible results in three decades’ time? One of the factors involved is the culture of technological optimism and a limited techno-economic rationality. Shouldn’t other factors like social, political, and ethical issues be included in our decision making models? Finally, energy models appear to be inadequate. They so far consistently underestimate renewables growth. Absolute displacement of fossil fuels is not yet in sight there. But of course: this would mean that existing energy infrastructure would not be able to run until their expected end of life. More realistic models might well conclude that they need to retire early.

The Ostrich and Phoenix cluster

This last cluster is that of commonly held beliefs. It justifies inequity, carbon-rich lifestyles and ‘social imaginaries’: collective images of how we might live. Evidently, this is the cluster that is most vulnerable to new concepts. Like concepts and convictions that could end the present stalemate on global emissions reduction. Therefore, we might well start here.

The first of these convictions supports inequity. Literature shows that inequity decouples the vulnerable from the powerful; that inequity erodes social trust required for collective action; and that inequity reinforces the preference of elites for a status quo hostile to climate action. We should bear in mind for instance that the wealthiest 1% of the world’s population are responsible for twice the emissions of the poorest 50%. Such disparities trickle down the entire social structure. But life-threatening harm from climate change tends to concentrate in marginalized communities. Effective climate policy options on the other hand tend to spread the burden. They would discourage flying frequently, driving SUVs, building large homes, or owning multiple cars (not to mention owning mansions and private jets). Inequity is in the present system.

As for implicit support for carbon-rich lifestyles: proposals focus mainly on technological substitution and behavioural change. They focus inadequately on factors that normalize and expand high-carbon lifestyles. There are large variations in emissions between different lifestyles, even within similar social groups and geographic regions; but so far, high emitters and emission-intensive lifestyles have not been targeted by proposed mitigation measures.

Can we imagine a comfortable future with less global emissions?

These factors are supported by our inability to imagine comfortable low-carbon lifestyle futures. Our collective images of how we might live in the future tend to look much like our present lifestyles. Insofar as energy comes into play, considerations tend to focus on policy issues, such as national security, or on cost-benefit relations. Issues of climate justice, racial justice, and gender equality are rarely being considered. This contributes to a mistaken belief that new images of how we might live, will be less comfortable. Tending to stifle action.

Taken together, this all contributes to an existing paradigm of ‘progress’, strong enough to resist change. The resulting social dynamic marginalizes alternatives and tends to promote high-carbon futures. We are caught in a self-reproducing image of a society that can only thrive through lots of energy.

As a consequence, the authors call for ‘plurality and more divergent thinking’. And leadership that will promote this. We need to be more aware of the scale and urgency of climate change. In order to better regulate corporations and dismantle heavily emitting industries. We need to be aware that only a small portion of the world’s population, as of existing industries, contributes to the vast majority of global emissions. ‘Climate change and the broader ecological crisis more profoundly call for a politics of humility, where we resituate ourselves as participants in a larger living system rather than as abstract from it.’

In the end, it’s a question of worldview

Our worldview has become dominated by ‘financial metrics and indices’. It has been proven hard to take into account ‘externalities’ like climate change caused by global emissions. So far, the authors write, ‘the power and inertia of the existing system have been sufficient to give the impression of ongoing control.’ The challenges are ‘recognized’ and ‘internalized’, but the real world hasn’t changed much. Witness the continuous growth of global emissions.

Nevertheless, the authors see some proof that people start to question the rationality of present developments. Climate change can no longer be hidden; people start to ask uncomfortable questions. We approach a critical tipping point. Whatever direction we will choose, the future will be quite different from the present. Either mankind succeeds in making radical decisions that will change society; or climate change will result in chaotic impacts that will destabilize society. ‘Within both of these futures, the existing power structures and paradigm associated with the Davos cluster are simply unfit for purpose.’

The most recent global climate conference, in Sharm-el-Sheikh, again failed to deliver the necessary radical results. Long-run business-as-usual sociocultural and political-economic norms continue to dominate the global state of affairs. As a consequence, future measures will need to be even more radical than before.

Interesting? Then also read:

Strong climate policy or freedom to consumers?

Climate discussion lacks sense of urgency

Roundup discussion: much like the climate debate