Is Europe still the world leader in climate issues? The continent has ambitious plans. But in the field of energy transition, things do not play out as planned. Europe may be overtaken by the US – although this might not be the most likely development under president Trump. But China is on the move. Moreover, not all European plans excel in credibility. Europe has difficulties in the field of costs, is dependent on raw materials and has a complicated system of permits. In short, there are many challenges, both in the field of adoption of this policy and in scaling up. Lux Research devoted a report on the state of affairs in Europe.

Obstacles on the way forward, according to Draghi

Mario Draghi, the former prime minister of Italy and former president of the European Bank, published a report on the future of European competitiveness. Broadly speaking, he says, there are three options: exit, paralysis and integration. Meaning: Europe decides not to play a role any role on the global scale, or to stagnate, or play a stronger role in international business.

European regulation is at the heart of the matter. In important issues like the Internet of Things and cyber security, Europe lags behind a lot. According to Draghi, there are too many rules in Europe. These stifle innovation and stand in the way of European attempts to keep up in the field of digital transformation. The EU has a strong tendency towards too many rules. Not just in the field of digital technology, but also in the field of energy. This is decisive for the European competitive climate.

Regulation of the energy sector

Regulation of the energy sector

In December 2019, the EU concluded the Green Deal. This was a comprehensive system that would lead to net zero emissions in 2050. In subsequent years, the EU formulated new benchmarks and strategies, intended to arrive at net zero emissions in many industries.

Politicians hailed this approach. The chairwoman of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, also expressed her faith in it. She suggests that the EU might even arrive at its goal of 55% emissions reduction in 2030. But even in spite of political optimism, data hardly underpin these conclusions.

EU greenhouse gas emissions

Since 1990, the EU has succeeded in reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 30%. But in order to arrive at a 55% reduction in 2030, efforts will have to be stepped up. Until 2030, solar and wind energies will be able to deliver their part.

But after 2030, this will be much more difficult. The, hard to decarbonize sectors like heavy industry and aviation need to adapt. This isn’t just a matter of policy but also of technological development. This last item will be decisive for the EU to meet its ambitious goals. In addition to that, the sectors themselves need to change. But it is a moot question if they are really willing to do so.

Over the past few years, the EU has adopted laws with specific targets for technologies judged to be critical. We find such technologies over the entire value chain, from fuels production with a low carbon content down to applications such as in buildings, transport and industry. The most important sectors are aviation fuels, energy storage and low-carbon hydrogen. These represent the most important and at the same time most demanding aspects of the transition.

Sustainable aviation fuels

It seems unlikely that the EU will meet its goal for sustainable aviation fuels by 2030. The goal is to produce 3.3 billion litres in 2030, but present capacity is just 300 million litres. Moreover, actual production is much lower. There is a major gap between the goal and the present state of affairs. It is unlikely that in the coming six years, the EU will meet its goal.

Lux Research suggests

- Policy stimuli. Sustainable aviation fuels are more expensive than fossil kerosine. Tax incentives might cover the difference.

- Lack of supply of feedstock. At present, waste fats are the feedstock, but this is in limited supply.

In order to make up for these constraints, tax incentives might be useful. And we need to develop alternative technologies to convert biomass into jet fuel.

Energy storage

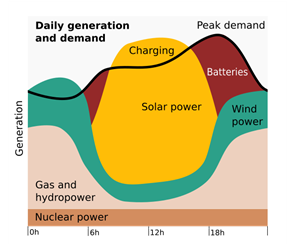

Energy storage is essential for the EU to achieve its 55% emissions reduction by 2030. But present storage capacity falls far short of what would bee required. Europe now has 20 GW of storage, whereas 200 GW would be needed by 2030, and 600 GW by 2050. Most existing storage is pumped-storage hydroelectricity, effective but limited by geographical constraints. To this, Europe must add technologies like electrochemical, mechanical, and thermal energy storage.

But there are substantial barriers to new solutions. Like

• Policy gaps. Developers are uncertain about revenue streams and market integration. Regulatory improvements often fall short, because member states have different grid systems.

• Lack of incentives: Energy storage receives less financial support than renewables like wind and solar.

• High costs.

Policy improvements that could make up for these barriers include

• Expanding the applications of energy storage. Like longer-duration storage, microgrids for resilience, and backup systems for industrial users. C;ear market regulations will be important.

• Cost reductions, by development of new storage options.

Low-carbon hydrogen

The EU has two key targets for green (or low carbon) hydrogen by 2030: produce 10 million tonnes domestically, and import an additional 10 million tonnes. But present production capacity is just 37,000 tonnes, and no hydrogen is being imported. With just six years left to 2030, it’s clear the EU is very far behind.

Green hydrogen is critical to decarbonizing industries and achieving the EU’s net- zero goals. But significant barriers prevent its widespread adoption:

- Green hydrogen is expensive. Industries do not want to pay a premium.

- Production costs are high.

- This might be offset if other regions, such as the Middle East and South America, would be willing to produce hydrogen.

The challenge

Draghi’s report outlines a number of obstacles facing the EU. Firstly, there is the question of international competition. How will Europe be able to set net zero targets and still be competitive with the US and China? Building and operating in the EU is much more expensive than in these tow countries. It does not produce many critical materials itself and therefore needs to revert to imports. There is a lengthy and cumbersome permitting process, which tends to delay projects and increase costs.

A central problem that Draghi touches upon is the difficult follow up between innovation and commercialisation. Europe does not excel in bringing new technologies to the market. Even in sectors where it has an advantage now, like wind and geothermal energy, it may lose its favourable position. Draghi stresses that the EU should not only innovate but also effectively apply its innovations. .

Key Takeaways

Draghi formulates three takeaways. We cite them in full.

1 The EU is on track to miss all its net-zero technology targets for 2030, possibly for 2050. A combination of weak policy support, lack of technology readiness, and low market adoption holds back net-zero technology in the EU.

2 Cleantech will be key for the EU to retain global leadership. By focusing on what needs to be done in the innovation space, companies can further enable the adoption of these technologies and help achieve net-zero goals.

3 Scale, don’t just innovate. Companies must focus on scaling cleantech from lab and pilot stages to full commercial deployment.

Interesting? Then also read>

Cleantech has much more economic potential than just low CO2 energy technologies

Towards net zero carbon emissions

The energy transition is a digital transition too