Resistance towards innovative changes is a well-known problem. It troubles many researchers and entrepreneurs, also those who venture into the biobased economy. The science of systems innovation deals with the question how to overcome such resistance. The latest term coined in this science is panarchy, the controlled empowerment of active small groups. As explained by Derk Loorbach in his inaugural lecture at Erasmus University, Rotterdam.

Lock-in and lock-out

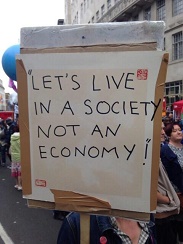

‘The way we have successfully organised society over the last century is fundamentally unsustainable in its design,’ says Loorbach. ‘But only now we are starting to see the fundamental challenges.’ The three ‘engines of modernity’ that propelled developments in the last century (central control, fossil resources, and linear thinking) now start to show their inherent weaknesses. From 2000 onwards for instance, much added growth was fictional. Therefore we now witness growing tensions in our growth-oriented society. For instance, major problems surface in areas like waste management and health care. Although prevention might be more efficient and cost-effective than our present end-of-process problem solving, society is unable to bring about such innovative solutions. Even the pursuit of sustainability is ‘locked in’ in this ‘problem-industrial complex’, as it is often geared towards the optimisation of inherently unsustainable processes and structures.

Loorbach explores the possibility of a ‘lock-out’, based on three principles opposite to the prevailing ones: distributed control (two-way cooperation), renewable resources, and systems innovation. In short, panarchy, defined as ‘a new interconnected form of anarchism: self-organising networks’. Panarchy is part of Loorbachs quest for ‘strategies that facilitate the least disruptive pathways to new equilibria’. In defining this quest, he takes another focus than many systems innovation researchers. During the past decade, these paid much attention to the clash between innovators and incumbent powers, seeking ways to strengthen the innovators in their struggle. Loorbach recognises that not the struggle as such, but the ‘least disruptive pathway’ to change is the goal to be supported. The ‘process of transformative change’ that he looks for, would preferably pass through a series of ‘stable dynamic equilibria’ which he describes as ‘sustability’. (This is also a play of words: ‘sustainability’ minus ‘inability’ would equal ‘sustability’).

Loorbach explores the possibility of a ‘lock-out’, based on three principles opposite to the prevailing ones: distributed control (two-way cooperation), renewable resources, and systems innovation. In short, panarchy, defined as ‘a new interconnected form of anarchism: self-organising networks’. Panarchy is part of Loorbachs quest for ‘strategies that facilitate the least disruptive pathways to new equilibria’. In defining this quest, he takes another focus than many systems innovation researchers. During the past decade, these paid much attention to the clash between innovators and incumbent powers, seeking ways to strengthen the innovators in their struggle. Loorbach recognises that not the struggle as such, but the ‘least disruptive pathway’ to change is the goal to be supported. The ‘process of transformative change’ that he looks for, would preferably pass through a series of ‘stable dynamic equilibria’ which he describes as ‘sustability’. (This is also a play of words: ‘sustainability’ minus ‘inability’ would equal ‘sustability’).

Panarchy for less disruption

Panarchy would be more bottom-up than the present political and economic process. But Loorbach notes that public debate is already dominated by bottom-up processes, based on inclusivity, circularity and true values. However, these processes often lack continuity and impact. Therefore, the essential social innovation would be to develop more effective ways to organise society, leading to a more stable impact of this bottom-up movement. Where bottom-up innovations already start to acquire a foothold in society, it is often because many people with a formal post in organised society (notably civil servants) are quite active in citizens’ groups, thereby connecting the worlds of bottom-up and top-down. Panarchy would exist precisely at this junction. The idea implies a self-organising governance mix, in any combination of government, society and market required by the problem at hand and the people involved, and the phase of the transition. Therefore, panarchy will not only be more bottom-up than present society, but also more top-down than many proponents of bottom-up advocate. In order to enhance the self-organising governance mix required for the much-wanted least disruptive pathways towards transition.

People like Loorbach might find assistance in their quest in unexpected ways. Particularly, I have technological development in mind. For two centuries, since the development of the steam engine, society has been propelled by technologies with strong economies of scale. Undeniably, this favoured the much-criticised central control, as it put in a favourable position organisations with a wide span of control. But as technology now rapidly develops into a much more distributed mode, inspired by processes in living nature, this might well be in favour of smaller scale organisations. Technology has long been the bogeyman from the point of view of sustainability and of social inclusivity. But it now seems to develop itself into a rather benevolent force; and that might have radical consequences for the self-organising ability of society. On the other hand, the changes resulting from this process might not be as radical as those that the systems innovation scientists have in their panarchistic minds.