In his book The Revenge of Gaia (2006) James Lovelock reasserts his idea that the earth, living and mineral, is a self-regulating system. A system that is now put to an extreme test by mankind by the vast amounts of CO2 we pump into the atmosphere. Lovelock argues with great mastery of his subject; but remarkably, as soon as he strays from the path of science and starts to argue on energy policy, his arguments lose their rigour and become as good as the next-door neighbour’s. Most interesting, nevertheless.

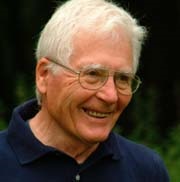

The Revenge of Gaia, Why the Earth is Fighting Back – and How We Can Still Save Humanity was among the books that I took from the bookshelves of Paul Reinshagen, my good friend and co-editor of this site, who passed away much too early. Never having read anything by Lovelock (but much about him), I rather expected a grim essay, Lovelock’s revenge so to speak, knowing the fierce opposition to his ideas among scientists, and certainly in view of the doom-spelling title. But here was this very kind then 87 year old author, in every inch a gentleman, who does not attack anyone in particular and even thanks an opponent like Richard Dawkins for the clarity of his argument.

The precarious condition of Gaia

For purely selfish reasons, Lovelock argues, mankind endangers the stability of Gaia, the entire system, by emitting huge quantities of that ultimate poison, CO2. Many species have become extinct already, many more will follow them; we may even make the planet uninhabitable to ourselves within a few decades, apart from some areas around the poles. This very hot world may become very violent, with warlords in permanent battle over the few remaining resources. Gaia will certainly survive, in some form or another; but if and how it will still be a place for mankind, is very much the question. Lovelock’s concept of Gaia as the ultimate self-regulating system on which all life on earth is dependent, implies ethics in which the wellbeing of Gaia, not of mankind, let alone the individual, is the ultimate good. ‘Gaia is an evolutionary system in which any species, including humans, that persists with changes to the environment that lessen the survival of its progeny is doomed to extinction…. We have in a sense stumbled into a war with Gaia, a war that we have no hope of winning. All that we can do is to make peace while we are still strong and not a broken rabble’ (p.139-140).

But, one might argue, the IPCC foresees much less damage, and is much less alarmistic. True, but here Lovelock has an independent judgment as a scientist. He argues that it seems inescapable that CO2 concentration, now 400 ppm, will rise to 500 ppm. During the past million years, this concentration has never been so high – as testified to by ice core analysis from Greenland and the Antarctic. We will have to go back to the Eocene, 50 million years ago, to come across CO2 concentrations this high. And then, the earth was 5 to 8 degrees hotter than it is now, largely made up of uninhabitable deserts. Lovelock squarely judges we are heading there. Considering the many possible drivers for further heating once we passed a certain threshold: more absorption of sunlight as ice caps melt, release of vast quantities of methane from the ocean beds and from underneath the tundra; and in the absence of clear countervailing feedback mechanisms to limit further heating. And yet – the CO2 concentration is at an alarmingly high level already, and although there is a well-established correlation between CO2 concentration and global temperature, we do not see the climatic consequences historically corresponding to it. Therefore, scientifically we are in a perplexing condition: will the earth still be heated up to an uninhabitable level, but with an unknown delay? Or are there unknown feedback mechanisms that will save us, so to speak, although we do not know for how long? Too many unknowns here. In risk theory, the unknown unknowns are the most awkward parameters to deal with. Although he later admitted that he had been ‘too alarmist’, in the book Lovelock simply sticks to the known history of Gaia and presumes that we have already passed the threshold; a position that he argues both gently and forcefully.

But, one might argue, the IPCC foresees much less damage, and is much less alarmistic. True, but here Lovelock has an independent judgment as a scientist. He argues that it seems inescapable that CO2 concentration, now 400 ppm, will rise to 500 ppm. During the past million years, this concentration has never been so high – as testified to by ice core analysis from Greenland and the Antarctic. We will have to go back to the Eocene, 50 million years ago, to come across CO2 concentrations this high. And then, the earth was 5 to 8 degrees hotter than it is now, largely made up of uninhabitable deserts. Lovelock squarely judges we are heading there. Considering the many possible drivers for further heating once we passed a certain threshold: more absorption of sunlight as ice caps melt, release of vast quantities of methane from the ocean beds and from underneath the tundra; and in the absence of clear countervailing feedback mechanisms to limit further heating. And yet – the CO2 concentration is at an alarmingly high level already, and although there is a well-established correlation between CO2 concentration and global temperature, we do not see the climatic consequences historically corresponding to it. Therefore, scientifically we are in a perplexing condition: will the earth still be heated up to an uninhabitable level, but with an unknown delay? Or are there unknown feedback mechanisms that will save us, so to speak, although we do not know for how long? Too many unknowns here. In risk theory, the unknown unknowns are the most awkward parameters to deal with. Although he later admitted that he had been ‘too alarmist’, in the book Lovelock simply sticks to the known history of Gaia and presumes that we have already passed the threshold; a position that he argues both gently and forcefully.

Lack of logical clarity

But then, when he switches to the role of a responsible citizen, and tries to sketch where to go from here, the compelling nature of his arguments vanishes as snow before the sun. The great man stumbles around in the area of energy policy just like most people do, lacking logical clarity and consistent priorities. It is not his support for CO2-free nuclear energy (that I do not share) that leads me to this judgment, but rather his utter neglect of energy inefficiency and what we could do about it. Surely, if we look upon CO2 as the ultimate poison, it should enrage us that so much CO2 is vented to the atmosphere for no good reason at all: because of insufficient insulation of homes and industrial piping, inefficient machinery, and most of all simple neglect? But Lovelock just devotes one unremarkable passage to energy inefficiency – as most half-informed citizens and policy makers would do. And Lovelock’s simple dismissal of solar energy (too expensive) shows no great knowledge of the laws that govern technology development. He has high hopes for the elusive world of nuclear fusion but does not see the benign opportunity around the corner.

Lovelock’s criticism of the humanist concept of sustainable development (or what we have made of it) and of the Christian concept of stewardship (both ‘flawed by unconscious hubris’, p.176) is very apt. So is his portrayal of biomass as an energy source that would even do further damage to Gaia if deployed on a large scale. And his criticism of our habit to use the land surface ‘as if it was ours alone’. He gave me food for thought as he highlighted that we go at great lengths to protect us from radioactive waste and do very little about CO2 that he judges to be the greater evil. And Lovelock even let me consider in a positive way some kinds of climate engineering, like creating just a little mist over our oceans. But above all I value him for his most gentle way to propose unselfishness as the ultimate goal, not for mankind, but for life as such, for Gaia.